‘The photographer no longer speaks the language of chemistry, but that of poetry’ — F. Holland Day

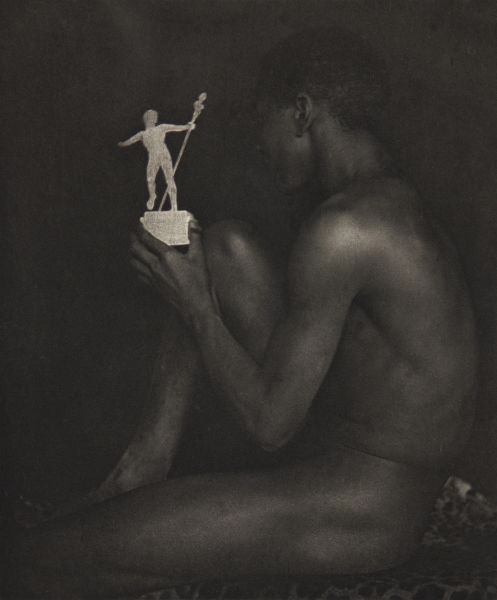

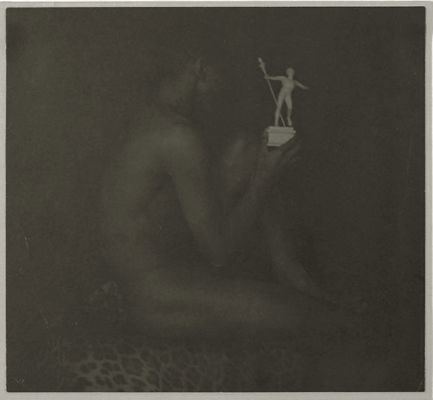

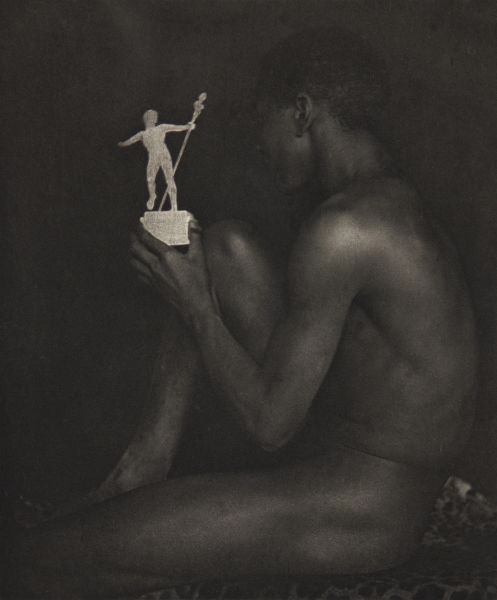

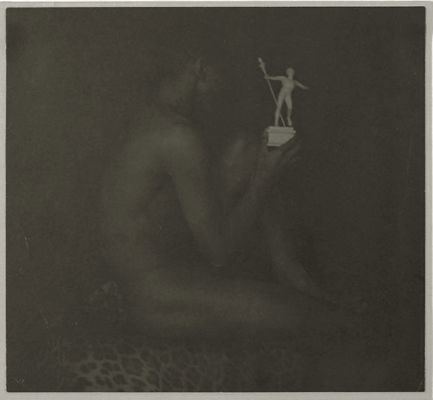

Ebony and Ivory, photogravure from American Pictorial Photography Series One portfolio, 1899.

Few pictorial photographer’s images were better suited for photogravure than F. Holland Day’s images of Alfred Tanneyhill, a black household helper. Wallowing in shadows and lacking definition, Day's controversial photographs of Tanneyhill were nothing less than visual tone poems - perfect for the smoky atmospheric syntax of photogravure. In Ebony and Ivory, Tanneyhill perches gracefully upon a leopard skin, his defined musculature and the luster of his body contrast with a white marble replica of a statuette he holds in his hand. By juxtaposing the seminude body with a classical symbol, Day established the dualities of nature and culture, Greek and African, and black and white.

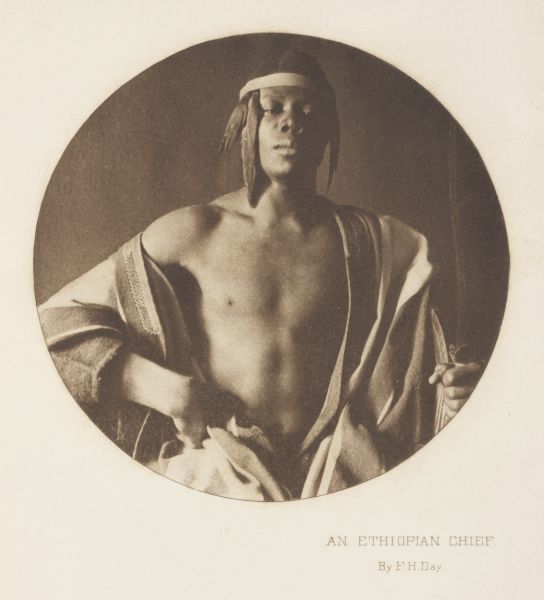

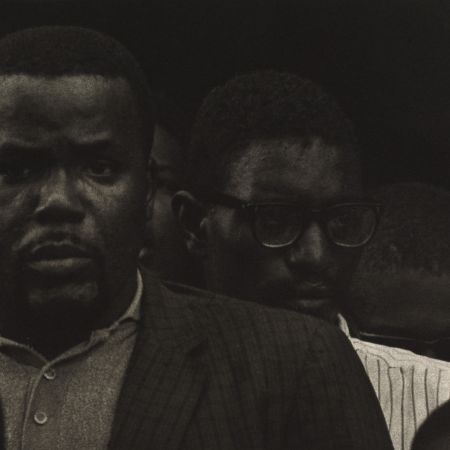

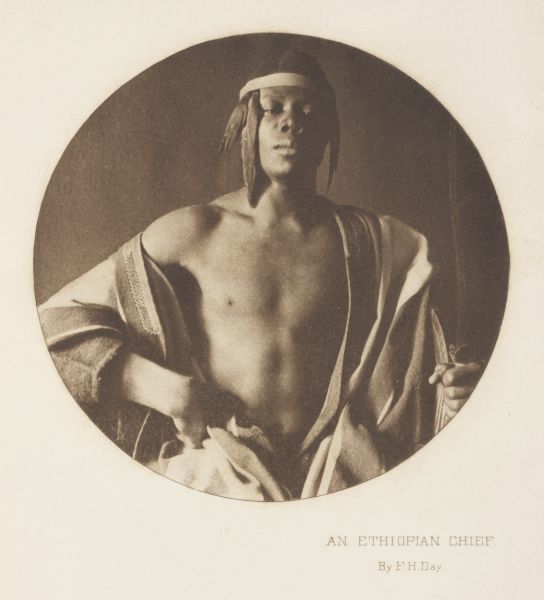

Day was a fastidious printmaker so when

Stieglitz featured his image,

Ethiopian Chief, in the first volume of

Camera Notes (October 1897), Day did not hesitate to find fault with the reproduction, complaining to Stieglitz that “it looked muddy”.

An Ethiopian Chief, Camera Notes Vol. 1 No. 2, 1897

No one thought more highly of Day’s work than Stieglitz who personally collected it in quantity, including a

platinum print of Ebony and Ivory now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Day commented to Stieglitz when sending him the print, “I think without exception the print is the most beautiful in tone which ever came from the negative. Its gradation of harmonies are wonderfully fine.”

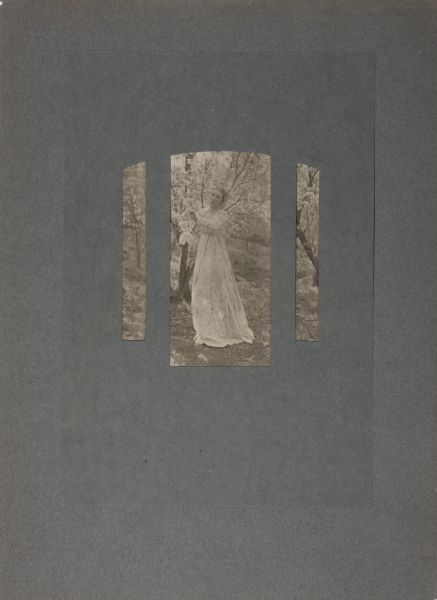

At the time, achieving parity between photogravures and original photographs was one of Stieglitz’s top priorities, and his desire for the photogravures of

Camera Notes to attain stature as independent works of art was paramount. He believed that one way

Camera Notes suffered was that the photogravures remained bound into journals. As a remedy, in 1899 he undertook a portfolio project entitled,

American Pictorial Photography. Repurposing

Camera Notes photogravures and legitimizing their artistic value, he mounted them to larger free-standing sheets and housed them in an elegant folio case. The edition was limited to 150 portfolios and

Series I was published in the fall of 1899.

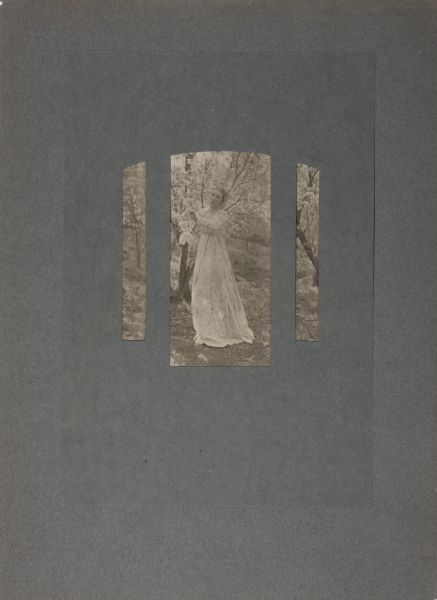

Clarence White, Spring from American Pictorial Photography, Series One portfolio. 1899

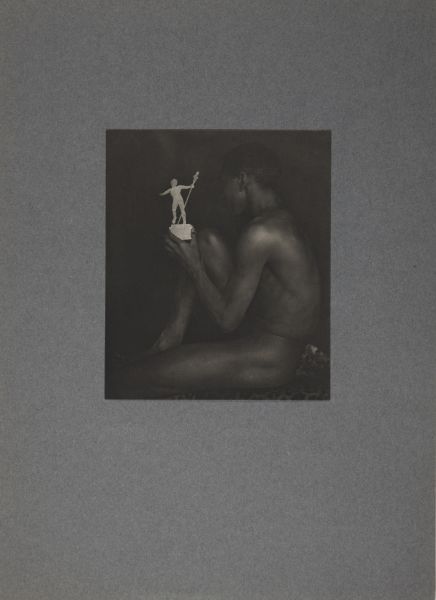

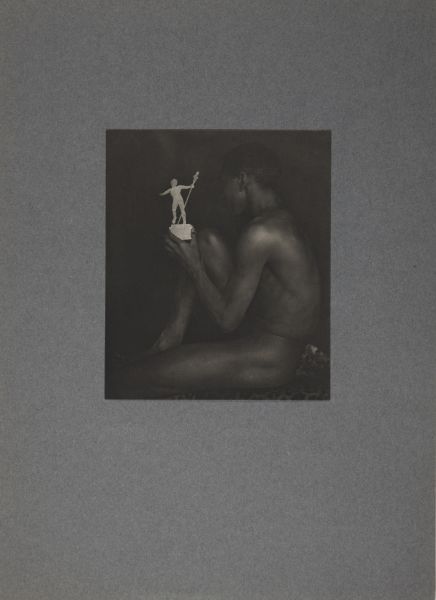

F. Holland Day, Ebony and Ivory, photogravure from American Pictorial Photography, Series One portfolio, 1899.

By the time Stieglitz published the first

American Pictorial Photography portfolio

Ebony and Ivory had already appeared in

Camera Notes (vol. 2, no. 1, 1898). And while it received praise in the press, Day must have again expressed his dissatisfaction to Stieglitz. Why else would Stieglitz have gone to the trouble and expense of making an entirely new photogravure plate. If not to calm or impress Day, perhaps it was to satisfy Stieglitz’s own high standards. Or had the plate worn too much making the

Camera Notes prints? For whatever reason, we should be grateful - the new plate was superior and the portfolio print is sublime.

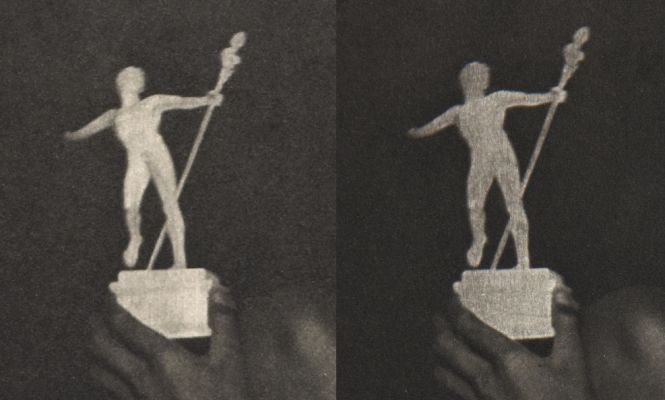

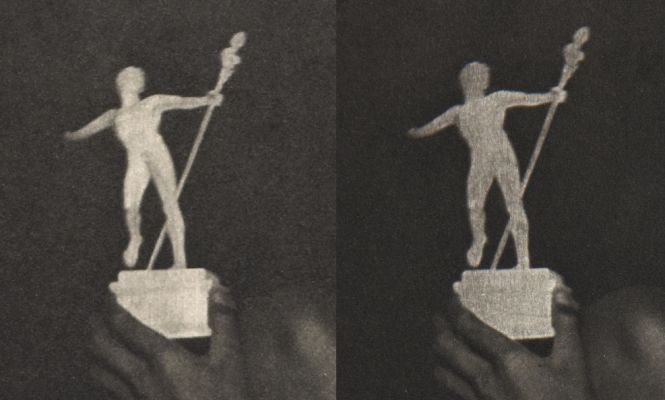

"'Ebony and Ivory’ is the most thoroughly artistic, the most finished piece of work that he [Day] has ever done. Its tonal -values are exquisitely harmonious, and in its conception it is distinctly Greek; indeed, it has but one fault that I can mention: The little ivory statuette is in too high a key of white for the subdued tones of the balance of the picture and is distinctly disturbing. Nevertheless, this is a minor fault, and the exquisite lines and modeling of the dusky figure, as it half emerges from its nocturnal background, are a source of constant pleasure." — Joseph Keiliey Camera Notes vol. 2, no. 3 1899

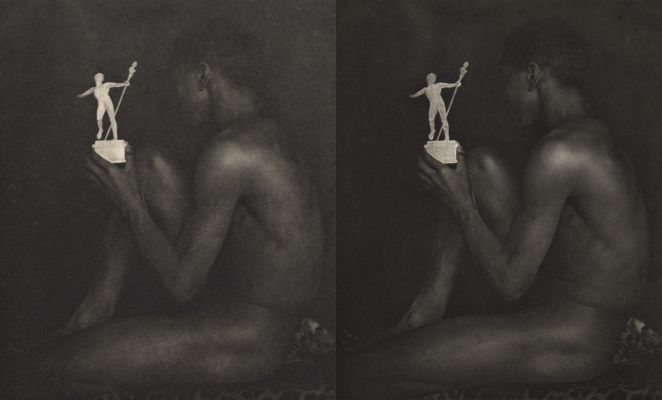

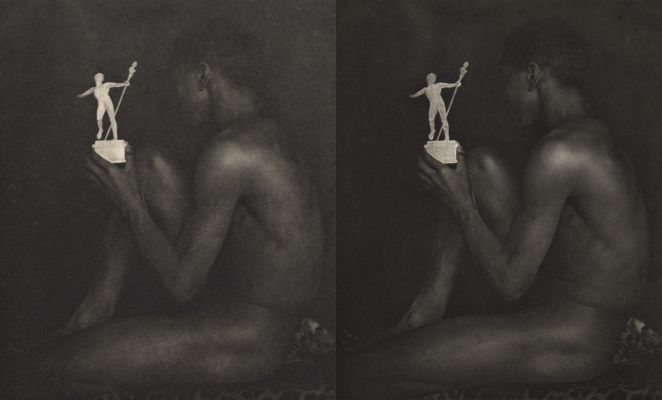

A comparison of the

Camera Notes photogravure and Day's

platinum print confirms Day’s intention was for the statuette to remain low in tone folding into the dark tonality of the image rather than standing out as it does in the

Camera Notes photogravure - an issue Stieglitz clearly attempted to rectify in the etching, retouching and printing of the

American Pictorial Photography plate.

F. Holland Day, Ebony and Ivory, Platinum, 18.3 x 20.0 cm, 1897 (the Met)

Camera Notes (left) vs. American Pictorial Photography (right)

Camera Notes (left) vs. American Pictorial Photography (right)

By the time

American Pictorial Photography was published, Stieglitz and Day had a ‘falling out.’ They had been butting heads over strategies to propel the American Pictorial movement forward. Critical of the New York Camera Club and

Camera Notes, Day broke rank and organized his own exhibition of prints by what he called the

New School of American Photography. While Stieglitz was successful blocking the exhibit in the US, Day found a home for it in London and Paris, ultimately threatening Stieglitz’s self-proclaimed position as leader of the American pictorial photography movement. Despite his near-reverential regard for Day’s work, Stieglitz clearly felt threatened by Day’s curatorial coup and he both obstructed and unjustly criticized the exhibition. Day apparently never forgave Stieglitz for his retaliatory actions, and from then on turned down Stieglitz’s requests for prints, permission to reproduce images, and use of his name, hence Day’s conspicuous absence from

Camera Work, scarcity of photogravures and gradual fade into obscurity.

As for the

American Pictorial Photography portfolios, so good was the printing and so effective was the presentation that to Stieglitz's delight, reviewers compared the photogravures to exhibition prints.

Joseph Keiley found them “so remarkably executed as to deceive the eye into the belief that they are original platinum and carbon prints and not merely reproductions therefrom.’’ And London’s Amateur Photographer stated: “In those cases in which the print has been trimmed and mounted on a tinted sheet, it is not easy to tell whether it is a photo-etched reproduction or a platinum print, so faithfully have the subtle qualities of the original been preserved."

While it is disappointing that Stieglitz likely turned Day off to photogravure, we can be grateful that the collaboration between the two at least resulted in this

beautiful rare print that we are fortunate enough to have in our collection.

References

Correspondence between F. Holland Day and Stieglitz. Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven Connecticut, Alfred Stieglitz Archives.

Correspondence between F. Holland Day and Stieglitz, Norwood Historical Society, Norwood, Massachusetts.

Day, F. Holland. “Art and the Camera”, Camera Notes, October 1897 (vol. 1, no. 2) p. 28

Fairbrother, Trevor. Making a Presence: F. Holland Day in Artistic Photography. Andover, Mass: Addison Gallery of American Art, 2012

Jussim, Estelle. Slave to Beauty: The Eccentric Life and Controversial Career of F. Holland Day, Photographer, Publisher, Aesthete. Boston: D. R. Godine, 1981

Naef, Weston J. The Collection of Alfred Stieglitz: Fifty Pioneers of Modern Photography. New York: Viking Press, 1978. pp. 72 – 78

Peterson, Christian A. Alfred Stieglitz’s ‘Camera Notes’. New York: Minneapolis Institute of Arts in association with W.W. Norton & Co, 1993.