Alfred Stieglitz & Camera Work

To quote scholar Estelle Jussim: "If ever there was a photographer with lofty aesthetic aims, it was Alfred Stieglitz [(1864–1946)], patron saint of 'straight photography', founder of the Photo-Secessionist movement, promulgator of abstract art and encourager of the avant-garde, idiosyncratic gallery owner, and resolute editor-publisher of one of the most famous of all photographic journals, Camera Work. It was here that the pantheon of early moderns was first widely reproduced: Clarence White, Gertrude Kasebier, Edward Steichen, Frederick Evans, Alvin Langdon Coburn, Frank Eugene, Robert Demachy, Joseph T. Keiley, and Stieglitz himself".

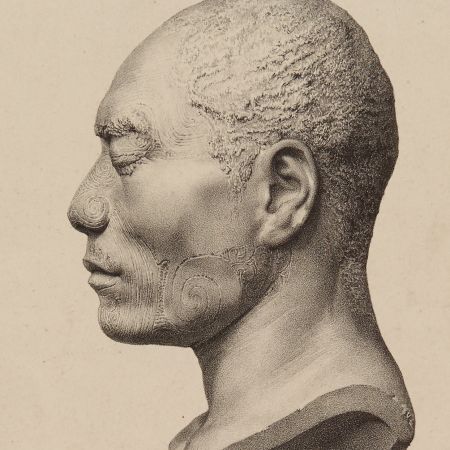

Annie Brigman, The Bubble, Camera Work XXV, 1901

"A dazzling array of photo-technologies was employed to convey the works of these photographers to an as yet indifferent public. Among these technologies were 'straight' photogravure... mezzotint photogravure, duogravures, one-color halftone, duplex halftones, four color halftones, and collotypes. Of these, photogravure was the predominant medium through the entire publishing venture of Camera Work, from its optimistically polemical beginnings in 1903 to its almost unattended extinction in 1917. These tipped-in, double-mounted, Japan tissue, individual plates were so magnificent that, as Jonathan Green observes, 'the reproductions in Camera Work are often finer than the original prints'".

Since many other pictures in Camera Work are photogravures from “original negatives,” we may be forced to consider the photogravure as a “direct medium,” just as the printing of a positive from a negative in a darkroom is said to be direct.

Photogravures recall the richness of mezzotints, the jet-black inks of lithography, the delicacy and fine lines of etching, and the decorative capabilities of aquatint. Indeed, at an historic exhibition of photo-technological methods held at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts in 1892, the name given to the photogravure process had been, precisely, “photo-aquatint.” This was by no means a misnomer, for the photogravure is essentially based on the properties of aquatint, in which the reticulation of a powder on a metal plate provides a wide variety of dot structures, varying in size and depth, which are etched with acid to produce an intaglio printing plate. While the name “photo-aquatint” did not last, the process was promptly acclaimed as the most beautiful, silky, dense, and rich of all the photo-technologies, as permanent as the oil-base carbon ink which Gutenberg had created.

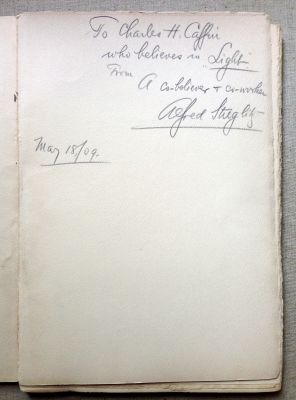

Camera Work XXVII inscribed to Charles Caffin

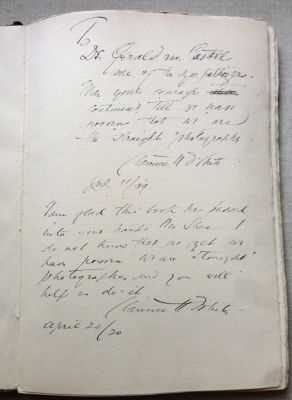

Camera Work XXIII inscribed twice by Clarence White

True to Stieglitz’s larger purpose of raising photography to the heights of more traditional fine arts, the reader of Camera Work was clearly invited to respond to the plates as if they were original prints. Stieglitz depended on the photogravure’s ability to beautifully present the work of Cameron or Eugene, and also to connect photography to etching and aquatint by the intaglio richness of printer’s ink. Once convinced that the hand of an artist was at play in the production of a picture, perhaps critics of the medium would give up their persistent harping on the contemptible mechanical aspects of the camera.

We are grateful to have a complete set of Camera Work in this collection. The set has been assembled over the past fifteen years and contains issues deaccessioned from The Paul Strand Archive, The Museum of Modern Art, The Estate of Dorthy Norman and Joanna Steichen. Inscriptions and signatures include those from Stieglitz, Steichen, Strand, White, Annan, Davison, and Coburn.

This site provides comprehensive, unique access to both Camera Work's images as well as its treasure trove of critical texts.

References

The content of this page has been adapted from:

Estelle Jussim (1979) Technology or Aesthetics: Alfred Stieglitz & Photogravure, History of Photography, 3:1.