These prints are remarkable for their fine detail, but not, one could argue, fully objective. — Philippe Foliot

History remembers

Honoré d’Albert, duc de Luynes, as an avid supporter of the arts, a passionate archeologist, and a patron of photographic activities—a man who dedicated his life to scientific endeavors of all types. Most famously, in 1856 he initiated an international competition to rectify issues facing the stability and reproduction of photographic prints

. Ultimately, the duke wanted to find a way to reproduce photographs in permanent printer’s ink without the intervention of manual retouching. The duke possibly started the competition in anticipation of his own publication,

Voyage d’exploration: la Mer Morte, which became a landmark in the history of science, art, and photography. The competition and the

Mer Morte are testaments to the challenges that faced photography in the mid 19th century and, further, the extensive efforts made to solve them.

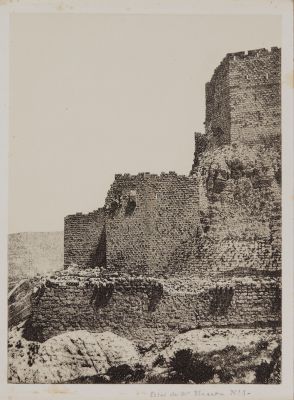

In 1864, eight years into the Duc de Luynes (DDL) contest, the duke and naval navigator Louis Vignes embarked on the first phase of the

Mer Morte expeditions to largely unexplored Christian sites. As the expedition’s photographer, Vignes faced many challenges; the blistering heat, dust, wind, and rugged environment made photographing on site difficult, especially as the locations were far away from any source of supplies. Even under the best of circumstances, creating serviceable negatives would have been a challenge. Vignes primarily used glass negatives, though the many surviving results were sub-par. While Vignes had proved competent in making

paper negatives of Middle Eastern subjects in the 1850s and early 1860s, his lack of experience with glass negatives resulted in poor exposures, fading, multiple losses, and other unintended effects like solarization.

Louis Vignes, PL. 16 Tyr: Brise-Lames du Port Égyptien, 1871

Photogravure executed by Négre for Voyage D’Exploration a La Mer Morte

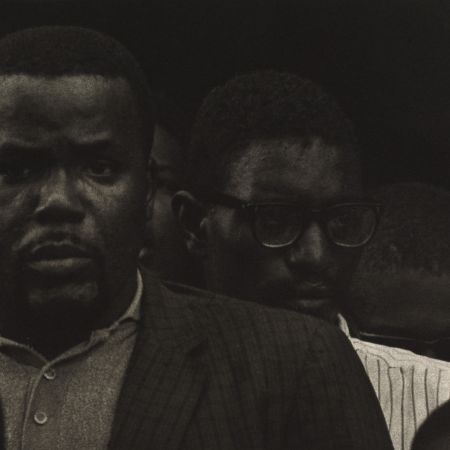

Charles Nègre, one of the finalists in the DDL competition, had been successfully experimenting with photomechanical processes for more than a decade. The duke, well acquainted with the quality of Nègre’s work, commissioned him in 1865 to produce photogravure plates from the troubled Vignes negatives. With the contest still undecided, it is no surprise that Nègre went to extremes to turn Vignes wanting negatives into beautiful, photogravure images. Employing his skills as a painter, Nègre transformed the photographs into “images of great poetry.” By comparing Vignes’ albumen prints with the photogravures in their final published state, one gets a sense of the complex retouching behind Nègre’s productions. Scholar Jacob W. Lewis explains:

“Nègre sought not only to correct perceptible defects, and embellish the appearance of skies and seas, but also to make sure the historical information recorded by the camera was framed by a general harmony of effect that neither detracted nor altered the photographic image’s documentary intent.”

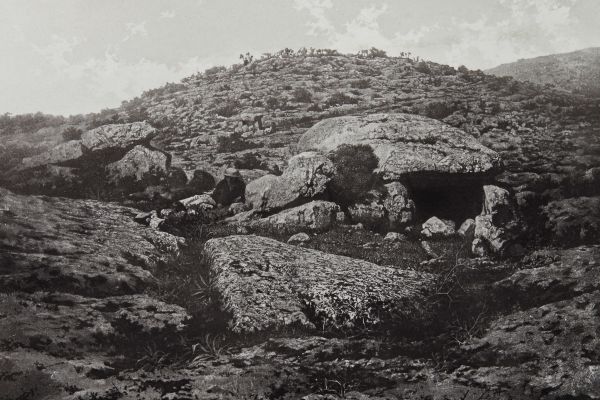

Louis Vignes, Manfoumieh, 1865

Albumen

Louis Vignes, PL. 40 Manfoumieh, 1871

Photogravure as it appeared in Voyage D’Exploration a La Mer Morte

“They were to produce proof, considered as irrefutable, of scientific observation.”

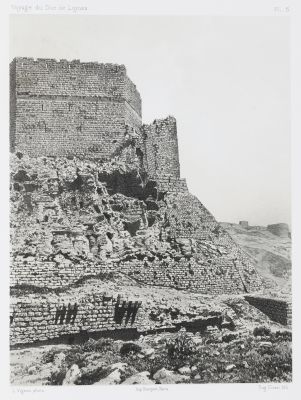

Louis Vignes, Arak-El-Emir, 1864

Albumen

Louis Vignes, Arak-El-Emir, Charles Nègre test proof, 1865

Photogravure from the estate of Charles Nègre

Louis Vignes, PL. 33 Arak-El-Emir, 1871

Photogravure executed by Charles Nègre for Voyage D’Exploration a La Mer Morte

The duke’s choice of Nègre for the Mer Morte commission raises some intriguing questions. Most significantly, was Nègre awarded the project because of his ability to save Vignes’ images? And wouldn’t the duke have anticipated that Nègre’s extensive retouching of the images might be in direct opposition to the established goals of his competition? Did he use Nègre to repair Vignes’ prints knowing that the very act of doing so would diminish Nègre’s chances of winning the top prize? According to Lewis:

“Undoubtedly Nègre was crushed by the decision after his long years of labor, given at the expense of both his purse and his health… In a letter to the Society thanking it for the medal (second place), he remarked that he had submitted a number of examples that had not been retouched. Those that had been retouched were done at the request of the Due de Luynes, who had commissioned them. The fact that his process permitted retouching to improve upon the original photograph was, he claimed, surely an advantage.”

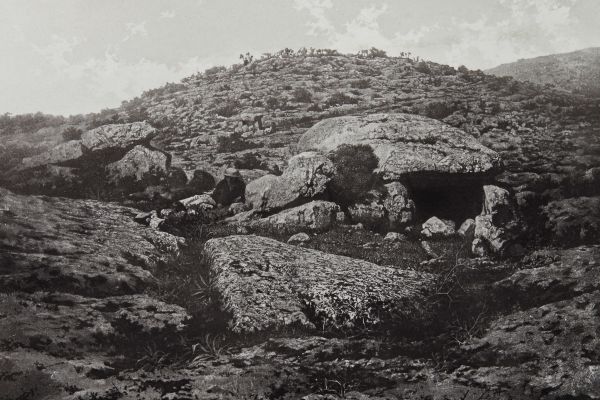

For the second trip of the expedition, from Jerusalem to Karak and Chabuk, the duke hired Henri Sauvaire to execute the photographs. Sauvaire, a pragmatic man and experienced technician, believed that using paper negatives would be easiest to handle in the challenging desert conditions. Sauvaire successfully returned from the trip with seventy-three technically competent paper negatives.

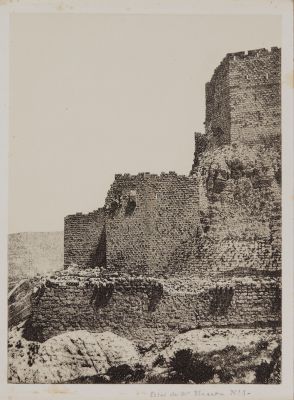

Henri Sauvaire, No. 44 Karak, 1866

Albumen

Sauvaire emerges as a real scientific photographer, full master of his technique… Sauvaire’s rate of failure was practically nil. — Philippe Foliot

In June 1866, the duke, who did not accompany the second expedition, wrote to Sauvaire thanking him warmly for his contribution to the project

: “Your talents as epigraphist and photographer have been instrumental in conferring great value on the exploration undertaken, by virtue of the authentic evidence with which you have provided it” (D’Albert de Luynes 7 June 1866)

. In subsequent letters to Sauviere, the duke stressed that he fully intended to reproduce his images by means of

“good heliograph engraving” but had not yet found a capable producer who could

“avoid any manual intervention in their reproduction… I am still obstinate in my efforts to have them engraved by heliography” (D’ Albert de Luynes 26 November 1866).

In his final letter to Sauviere, shortly before his death in 1867, the duke claimed to have found a viable option:

“I am most pleased to be able to tell you that I have at last found a good heliographic engraver whose work I find most satisfactory. I shall ask him on my return to effect (sic)

the engraving of at least 60 of your best pictures.” Could the “

good heliographic engraver” have been

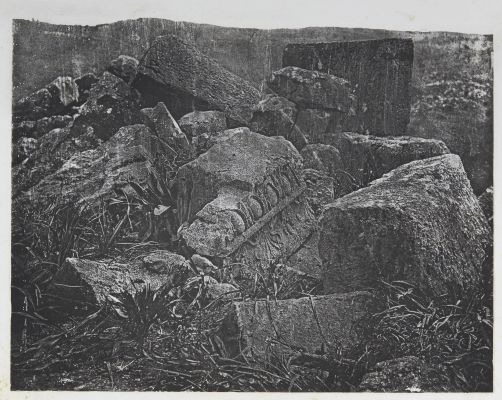

Paul Emile Placet? Placet, also a viable contestant in the DDL at the time, had made significant strides with his own photogravure process by the mid 1860s. Using negatives he acquired from the Bisson studio in 1864, Placet added text on many of the tests submitted to the competition

“Specimen sans Retouche d’Aprés Nature’’ to assure the judges that the work was not altered. Ultimately, Placet was eliminated from the competition because his process was an “assimilation” of other processes and, therefore, could not be considered original.

We have in our collection two heliographic tests, presumably essais

made for the duke by Placet from Sauvaire’s negatives. They are strong in comparison to the original albumen prints.

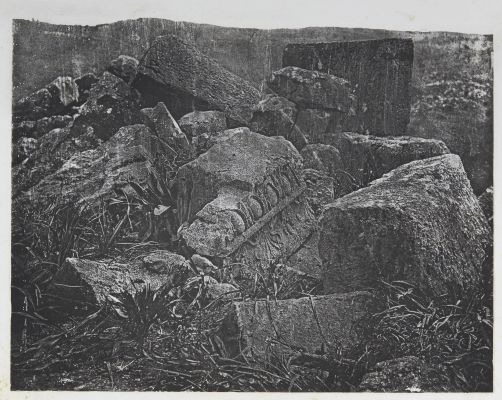

Henri Sauvaire, Essai de Mr Placet – No. 1, 1866

Photogravure

Henri Sauvaire, Essai de Mr Placet – No. 2, 1866

Photogravure

Unfortunately for everybody involved in the

Mer Morte project, the duke died in 1867. The duke’s eldest grandson, who had undertaken the completion of this opus, met his death in the 1870 war and, thus, the publication did not take place until 1875.

The process finally employed for the photographs from the second expedition fall way below the standards hoped for by the duke. Ultimately, Eugene Ciceri, who had acquired fame as a lithographer around 1865, reproduced the Sauvaire photographs. Without denying his artistic talent, the quality of his results fails aesthetically when viewed next to Nègre’s and scientifically next to Placet’s. The result is more like the illustrations for an adventure story than for a scientific work, and it could hardly have been what the Duc de Luynes had in mind when he wrote on 5th January, 1867,

"I have at last found a good heliographic engraver whose work I find most satisfactory.”

In the end, Nègre’s early mastery of the photogravure process ensured the lasting life of one of the most important archaeological projects in the second half of the nineteenth century. The results are beautifully immersive photographs that, to this day, reveal a rare, distant and lost world. One wonders what would have been had the duke’s descendants pushed Placet to complete the second half of the project.

We are fortunate to have ten Vignes albumen prints, two Sauvaire albumen prints, seven Placet photogravures, the complete Mer Morte Atlas, a rare intermediary stage photogravure test by Charles Nègre and a beautiful exhibition print of Vue Prise Audessus de Mar Saba in the collection.

References

Foster, Sheila J., Manfred Heiting, and Rachel Stuhlman. Imagining Paradise: The Richard and Ronay Menschel Library at George Eastman House, Rochester. Göttingen: Steidl, 2008.

Foliot, Philippe. “Louis Vignes and Henry Sauvaire, Photographers on the Expeditions of the Duc De Luynes.” History of Photography. 14.3 (1990): 233-250.

Jean-Mathieu Martini, “Voyage” February 2015, Daniel Blau.

Lewis, Jacob W. Charles Nègre in Pursuit of the Photographic, 2012.

Luynes, Honoré T. P. J. A, Melchior Vogüé, Louis Vignes, C Mauss, and Henri J. Sauvaire. Voyage D’exploration À La Mer Morte, À Petra, Et Sur La Rive Gauche Du Jourdain: Oeuvre Posthume. Paris: A. Bertrand, c. 1868–1874.

Nègre, Charles, and James Borcoman. Charles Nègre 1820–1880. Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada, 1976.

The Photographic Journal. London: Photographic Society of London, 1867.

Timeline:

1856 – Duke instigates competition

1859 – Date of contest extended

1862 – Poitevin wins petit prize

1864 – First Expedition – Vignes

Placet Purchases Bisson studio contents

1865 – Duke Commissions Nègre

Nègre begins work

1866 – Second Expedition – Sauvaire

1866 – Duke works to find alternative engraver to Nègre for Sauvaire Prints

1867 – Nègre sends proofs of DDL images to SFP jury

Poitevin wins DDLC for a process he had patented in 1855

Saulcy’s Book with Poitevin photolithographs of Salzmann photographs, Mémoire Sur La Nature

1867 – Duke dies

1871 – First installments of edition published

1874 – Final publication

1880 – Nègre dies