Annan’s Tests

I made the photogravure reproductions for my own satisfaction as I thought I could get more artistic results than the carbon prints.

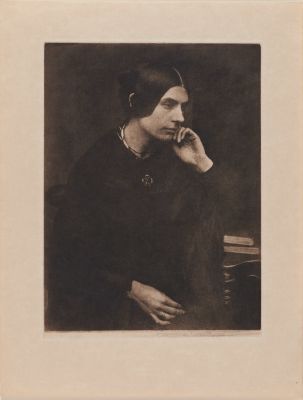

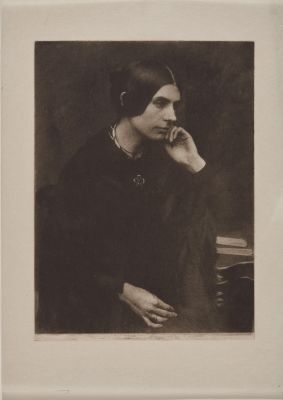

Lady in a Black Dress on velum, 28 x 22 cm

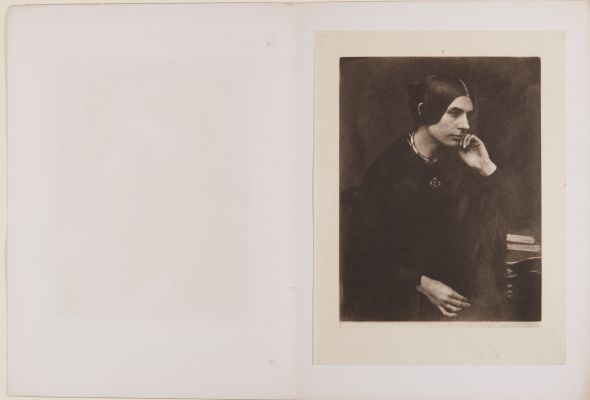

Lady in a Black Dress on tissue, 28 x 20.1 cm

Lady in a Black Dress in tissue mounted to light colored folder

In addition a few prints of the 20 plates were made and in a loose folder were sold to friends and admirers. These, still in deference to Elliot’s publication, were never advertised. I find there is one complete set remaining at Sauchiehall St. and if you care to have it the cost will be Five Guineas. I did not collaborate with anyone else in the production. There is no letterpress. The plates are probably still in good condition and further copies might be printed if – and when – the fine Japanese paper used again becomes available.

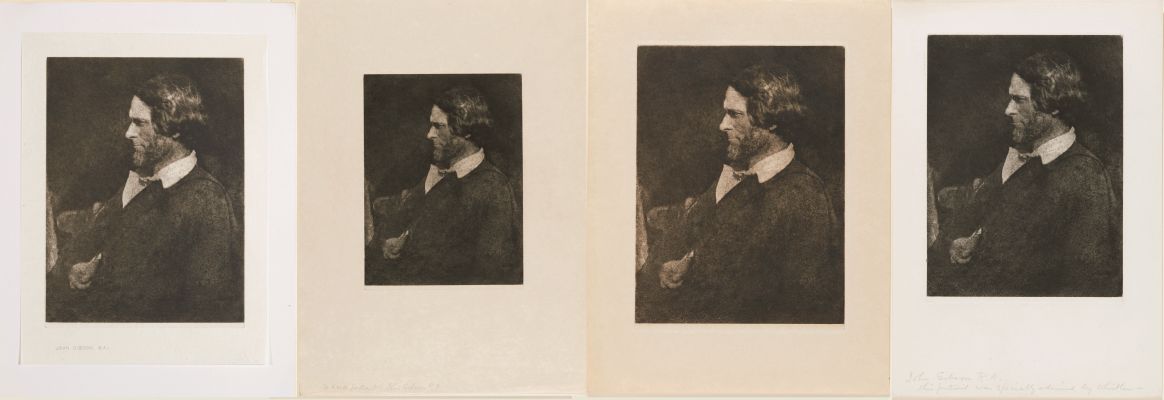

John Gibons R.A., four states

References

Annan, J. C., and William Buchanan. J. Craig Annan: Selected Texts and Bibliography. New York: G.K. Hall, 1994.

Annan, J.C. “David Octavius Hill, R.S.A., 1802–1870,”Camera Work, no. 11 (July 1905): 17.

Buchanan, The Art of the Photographer J. Craig Annan 1864–1946.

Gernsheim, New Photo Vision, London: Fountain Press, 1942.

Schaaf, Sun Pictures: Catalogue Eleven. New York: H.P. Kraus, Jr, 2002. Print.

McCauley, Anne. “Writing Photography’s History Before Newhall.” History of Photography. 21.2 (2015): 87-101.

Correspondence between James Craig Annan and Helmut Gernsheim regarding the Hill and Adamson photogravures are located at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas, Austin.