Title

Panorama parisienArtist

Nègre, Charles (French, 1820-1880)Key FigurePublication

De la série “Paris en miniature”Date

1961 plate (1852 negative)Process

Photogravure (heliogravure)Atelier

Charles NègreImage Size

6.5 x 6.8 cm

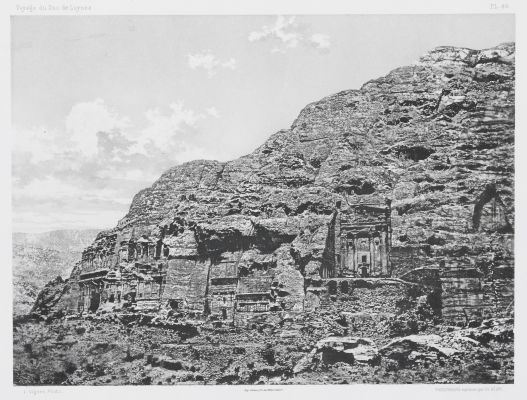

Charles Nègre became one of the early masters of photography after being encouraged to take up the medium as a study tool by his painting teacher, Paul Delaroche. After a short period of experimenting with daguerreotypes, Nègre started using the calotype (paper negative) process in 1847. In 1852 he documented the Midi region of France, ultimately establishing his reputation as a photographer of architecture. Like the many others dissatisfied with the fading qualities of salt or albumen prints, Nègre actively pursued alternative printing methods that could combine subtlety of tone with image permanence. In 1854, the massive experimentation with photomechanical printing in France gained the attention of Europe’s first photography journal, La Lumière, edited by Ernest Lacan. Like Nègre, Lacan had become convinced that, because of the impermanence of silver salts, the true future of photography lie in the use of printer’s ink. While the photogravure methods devised by Niépce de Saint-Victor and William Henry Fox Talbot could successfully reproduce simple, higher-contrast images, the results were unsatisfactory when applied to images with a subtle continuous tone. While a student of Niépce, Nègre attempted to perfect his mentor’s process by working to improve the photogravure’s tonal values, submitting his tests to Lacan and La Lumière along the way. Impressed by Nègre’s result, Lacan published two of his photogravure plates in La Lumière, emphasizing the importance of his work: These plates, not retouched, have a delicacy, a tonal transparency, a perfection that the most beautiful of daguerreotypes could never surpass. In seeing them, it is impossible not to recognize that photographic engraving is destined to revolutionize the arts.

Nègre presented his successes with the photogravure to the Académie des Sciences on December 18, 1854, an account of which La Lumière published shortly after. With the article, La Lumière printed Nègre’s view of François Rude’s relief Le Départ, from the Arc de Triomphe. Nègre took careful notes of all his experiments and tests, numbering and lettering them sequentially. The few surviving notes on these tests offer a rare insight into the challenges Nègre faced, as well as the progress he made. In February 1854, Lacan wrote of Nègre’s tests: “She is an Arlésienne sitting [sic] and reading, on the threshold of the old cloister of Saint-Trophime. When we have seen this ordeal, it had only been subjected to one bite, and yet the details stone walls gnawed by time and on which light traces thousands of drawings strange, have been reproduced better perhaps on the steel than in the photographic snapshot, remarkable for its finesse. Without editing this board, but submitting successively some parts very vigorous, but lacking in transparency, the action of the biting, tempered by the resin powder, the artist will make a complete work.” [1]

In the early 50’s, Ferrier and Soulier had taken many stereo views of Paris including the most famous buildings of the capital. Charles Nègre had used some half views for his project "Paris en miniature" to engrave the steel plates for the heliogravures.

This is a later test print made with a plate in the possession of Andre Jammes in 1961.

Reproduced / Exhibited

Borcoman, James. Charles Negre. Ottawa: Galerie nationale du Canada, 1976. Fig. 129.

https://collections.si.edu/search/detail/edanmdm:npg_AD_NPG.85.10?q=record_ID%3Dnpg_AD_NPG.85.10&record=1&hlterm=record_ID%3Dnpg_AD_NPG.85.10&inline=true

References

[1] Charles Nègre 1820-1880 et la gravure héliographique. Galerie Francoise Paviot / Paris

Borcoman, James, and Charles Nègre. Charles Nègre. Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada for the National Museums of Canada, 1976.

La Lumière: Revue De La Photographie: Beaux-Arts, Heliographie, Sciences. Paris, 1851.

Lewis, Jacob W. Charles Nègre in Pursuit of the Photographic, 2012.

Photography in Print : From the Photogravure to the Photobook, Bernard Quaritch ltd, Catalogue 1394.