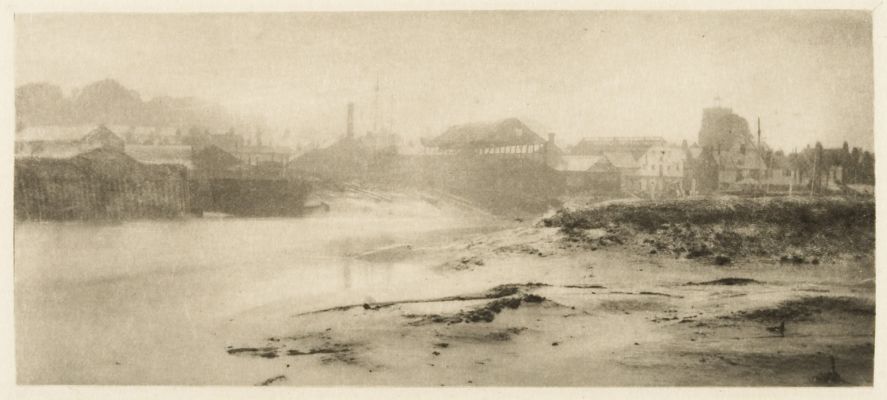

Title

The Onion FieldArtist

Davison, George (British, 1854-1930)Publication

Camera Work XVIIIDate

1890Process

PhotogravureAtelier

T. & R. Annan & SonsImage Size

15.4 x 20.4 cm

"The earliest impressionistic photograph." (Gersheim)

George Davison was one of the founding members of The Linked Ring Brotherhood, a group of photographers who severed their association with the Photographic Society of Great Britain to set up their own salon, feeling the concerns of the society to be too focused on technical issues rather than on matters of artistic merit.

Davison’s work was influenced by Peter Henry Emerson’s ideas of selective focus in photography which emulated the eye’s vision of nature. Davison adapted these theories to espouse an impressionist aesthetic. He believed photography to be in a unique position to evoke nature through direct experience which, when distilled by an artistic sensibility and handling of the medium, could provide an enhanced impression of nature by portraying its essence.

‘The onion field’ (originally titled ‘An old farmstead’) was the first impressionist photograph that Davison exhibited in 1890. He took the image using a pinhole camera – where a small hole on a piece of metal replaced an ordinary lens – which diffused sharp detail to provide an image of landscape through an overall soft focus, accentuated by the collective patterning of onion flowers.

While Emerson would come to resent his ventures into naturalistic photography when seeing its impressionist extremes in works such as Davison’s, it met the approval of Alfred Stieglitz, champion of a new generation of pictorial photographers, who reproduced ‘The onion field’ as a photogravure 17 years later in the pages of his illustrious journal ‘Camera Work’. [1] Art Gallery of New South Wales Photography Collection Handbook, 2007.

Reproduced / Exhibited

Beaton, Cecil, and Gail Buckland. The Magic Image: The Genius of Photography. London: Pavilion, 1989. p. 79

Newhall, Beaumont. The History of Photography: From 1839 to the Present. , 2012. p. 144.

Crawford, William. The Keepers of Light. Dobbs Ferry: Morgan and Morgan, 1979. fig. 77

Daum, Patrick, Francis Ribemont, and Philip Prodger. Impressionist Camera: Pictorial Photography in Europe, 1888-1918. London: Merrell Holberton, 2006. p. 68

Frizot, Michael. New History of Photography. Place of publication not identified: Pajerski, 1999. Print P. 295

Gernsheim, Helmut. Creative Photography. Aesthetic Trends 1839-1960. [with Illustrations.]. London: Faber & Faber, 1962. p. 122

Harker, Margaret F. The Linked Ring: The Secession Movement in Photography in Britain, 1892-1910. London: Heinemann, 1979. pl 3.4

Kruse, Margret. Kunstphotographie Um 1900: D. Sammlung Ernst Juhl; Hamburg: Museum für

Kunst u. Gewerbe, 1989 pl. 246

Morrison-Low, A D, Julie Lawson, and Ray McKenzie. Photography 1900: The Edinburgh Symposium. Edinburgh: National Museums of Scotland and the National Galleries of Scotland, 1994. fig. 16

Marien, Mary W. Photography: A Cultural History. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: SunSoft Press, 2002. fig. 4.7.

Sternberger, Paul S. Between Amateur and Aesthete: The Legitimization of Photography As Art in America, 1880-1900. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2001 p. 43

Stieglitz, Alfred, Richard Whelan, and Sarah Greenough. Stieglitz on Photography: His Selected Essays and Notes. New York, NY: Aperture Foundation, 2000. p. 40

Rosenblum, Naomi. A World History of Photography. New York: Abbeville Press, 2008. no. 366.

Weaver, Mike. British Photography in the Nineteenth Century: The Fine Art Tradition. Cambridge [United States: University Press, 1989. p. 227.

References

[1] Art Gallery of New South Wales Photography Collection Handbook, 2007.