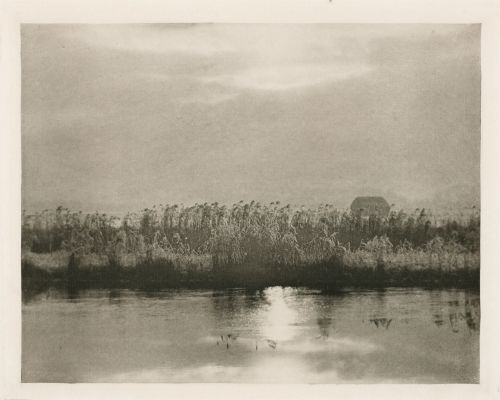

Title

The Misty RiverArtist

Emerson, Peter Henry (British, 1856-1936)Key FigurePublication

Marsh LeavesDate

1895Process

PhotogravureAtelier

Peter Henry EmersonImage Size

19.6 x 15 cm

Emerson’s final photographic book, the culmination of Emerson’s artistic development, Marsh Leaves was published five years after he renounced the belief in photography’s fine art status. In many ways paradoxically his most artistic volume, it is composed of most personal writings, only obliquely linked to his most exquisite images of pure landscape. Self-consciously composed as a conclusion for his decade in the photographic arena, it is his final statement of art and life, as well as a farewell to the private pictorial sphere that East Anglia had been to him. Emerson’s sixteen photo-etchings are delicate, lambent, and elegiac. The landscape is lovely but unreachable, wrapped in mist or touched by frost, unpopulated and nearing abstraction. Although emphatically rural and regional, unlike the cosmopolitan and international decadence of much fin-de-siecle art, its elegiac tone was perhaps responsible for its continuing relevance. Historians today see it as predicting the direction of the next century’s fine art photographic practice. [1]

“It is one of the most beautiful books about isolation and solitude, perhaps death, ever made, and Emerson’s spare, evocative pictures were seldom equaled by the later Pictorialists.”– Parr & Badger.

Although published in 1895, the photographs were taken before the end of 1891. The deluxe edition (bound in morocco and white linen) was limited to 100 copies while the ordinary edition (bound in blue cloth) was limited to 200 copies. A ‘popular’ edition was not illustrated. The total edition was 300 copies. The total edition was 300 copies; both editions are now very rare.

Emerson’s seminal work Naturalistic Photography for Students of the Art (1889) provided historical and critical foundation for a whole generation of photographers. In his writings, he advocated the photogravure as the perfect translation in ink of the aesthetic qualities of the platinum print, eventually learning to make gravures himself. Emerson’s admiration of the work of etchers like Whistler is especially apparent in Marsh Leaves, in which he experimented with both the high-contrast, sparse etching style of Whistler and Hayden, and the full tonal range inherent in photography. [2]

Reproduced / Exhibited

Newhall, Nancy. P. H. Emerson: The Fight for Photography As a Fine Art. New York: Aperture, 1976. (frontis) and p. 245.

Weaver, Mike. British Photography in the Nineteenth Century: The Fine Art Tradition. Cambridge [United States: University Press, 1989. p. 211.

MET Accession Number: 2014.301

Getty Object Number: 84.XB.696.7

References

[1]Imagining Paradise, p. 193.

[2] Hammond, Anne, The Etching Revival and the Photogravure: A Graphic Aesthetic for Photography; Impact 6 International Multi-Disciplinary Printmaking Conference

Newhall, Nancy. P. H. Emerson: The Fight for Photography As a Fine Art. New York: Aperture, 1976. p. 189.

Carl Fuldner, ‘Emerson’s Evolution’, Tate Papers, no.27, Spring 2017, http://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/27/emersons-evolution, accessed 26 July 2017.

Taylor J. The Old Order and the New : P.H.. Emerson and Photography 1885-1895. Munich: Prestel; 2006.

Goldschmidt Lucien Weston J Naef and Grolier Club. 1980. The Truthful Lens : A Survey of the Photographically Illustrated Book 1844-1914. 1st ed. New York: Grolier Club no. 54