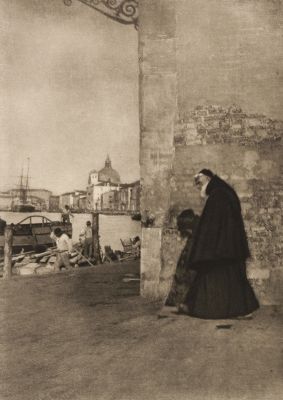

Title

The Dark MountainsArtist

Annan, James Craig (Scottish, 1864-1946)Key FigurePublication

Camera Work VIIIDate

1904Process

PhotogravureAtelier

T. & R. Annan & SonsImage Size

15 x 20.2 cm

The earliest dated print Stieglitz collected by one of his contemporaries. Stieglitz collected about sixty Annan prints, a number surpassed only by work by Steichen. [1]

The photograph was taken on Ben Vorlich, a mountain to the north of Loch Lomond. Its somber, introspective mood is typical for this period of Annan’s work and the result of his skilled use of the photogravure technique. How did Annan render so intriguing four men on a mountain ridge? They walk away, presenting their backs to the viewer who thus becomes one of their group. There is an invitation to follow them to the glow far ahead, across the ranges, under the lowering sky. He evokes half-forgotten ideas of quest or pilgrimage. His Dark Mountains is weird and solemn, shades of night are among the valleys, and the light or wintry dawn is breaking in the heavens. [2]

The Dark Mountains was described by critics at the time as full of grim purpose evoking Dantesque dreams, ideas of massive, awful grandeur, unknown threatening dangers. With its silhouetted figures facing a vast Scottish landscape, Annan’s image recalls the eighteenth-century aesthetic of the Sublime in nature. [3] Over the years, the subject matter of this image has been interpreted in different ways. Soon after its first publication in 1895, it was thought to refer to the Old Testament, in which Moses receives the Ten Commandments on Mount Sinai. In 1901, another critic read into it: "Dantesque dreams, ideas of massive, awful grandeur, unknown threatening dangers". By 1986 the image was described as a Romantic landscape in the tradition of the painter Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, also known as Wanderer Above the Mist. [4]

‘The Dark Mountains’ – the very name summons to our imaginations Walpurgian nightmares or Dantesque dreams, ideas of massive, awful grandeur, unknown, threatening dangers, the unexplored countries beyond, whence the last light of day flares up into the night-darkening sky. Such a light flares up into such a sky in Mr. Annan’s picture, and outlined against it we see in the distance a range of dark mountains massing against the beyond. Some figures in the foreground, draped Dantesque fashion, walk from us towards the mountains. Their heads are bowed, somewhat like pilgrims approaching some holy shrine, or men engrossed in all-absorbing thoughts. Their figures are indistinct and simply outline themselves in dim masses against the distance. Whence are ye, oh, silent travelers, and whither are ye bound? Follow ye the trail of Death over the range of Time in search of the Eternity beyond? Or are ye bent on Faust-like quest of horrid distraction from the ever present memory of some ill deed done that chafes the conscience and humiliates the soul? There are in the immediate foreground of this picture two white masses that may be rock masses or drifts of snow or glimpses of mountain streams, but which do not explain themselves and whose pronounced unexplained lightness disturb the quiet harmony of the picture. The sky towards the tops and sides, cspc^mixj w me icit, as we face the picture, is rather too densely and harshly rendered, and the transition from light to dark is too abrupt to be pleasing or thoroughly artistic. This picture, with the two previously mentioned, lose certain of their qualities through the manner in which they have been matted and framed. Differently exhibited, they would have shown to far better advantage. [5]

The whole looks like an Old Testament subject. Moses is certainly suggested, and if the rest of the actors do not fulfill the requirements of any particular scene in the patriarch’s life, the whole picture seems full of grim purpose. To explain it in prose would be to do it injustice, for the glamour Mr. Craig Annan has imparted to it should not be dispersed by ‘factual’ reporting. It is not perhaps great, still less a picture to be imitated, but as an experiment it is most interesting. Surely the reproach that the operator has but to put his head under a black cloth and let the camera do the rest, cannot be maintained before this artist’s work. [6].

Reproduced / Exhibited

Buchanan, William. J. Craig Annan: Selected Texts and Bibliography. Oxford: Clio Press, 1994.(cover)

Buchanan, William, and J C. Annan. The Art of the Photographer: J. Craig Annan, 1864-1946. Edinburgh: National Galleries of Scotland, 1992. plate 21.

Naef, Weston J. The Collection of Alfred Stieglitz: Fifty Pioneers of Modern Photography. New York: Viking Press, 1978. no. 9

Frank, Waldo D. America and Alfred Stieglitz: A Collective Portrait. New York: Aperture, 1979. pl. 31 (titled Mountaintops)

Simpson, Roddy. The Photography of Victorian Scotland. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2013. p. 167

Weaver, Mike. The Photographic Art. Edinburgh, 1986. no. 39

References

[1] Naef, Weston J. The Collection of Alfred Stieglitz: Fifty Pioneers of Modern Photography. New York: Viking Press, 1978 p. 260

[2] Buchanan, William. J. Craig Annan: Selected Texts and Bibliography. Oxford: Clio Press, 1994 p 27

[3] MET website cited Jan/2023 https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/269394

[4] Kelsey Robin. Photography and the Art of Chance. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press 2015 p. 111

[5] Keiley., Joseph T. ‘The Salon (Philadelphia Oct. 22-Nov. 18) Its Place, Pictures, Critics, and Prospects’. Camera Notes, vol. 4, no. 3 (Jan. 1901), p. 189-227. [p. 197-99].

[6] ‘The Two Great Exhibitions’. Photograms of ’95, p. 13-79. [p. 36-42].