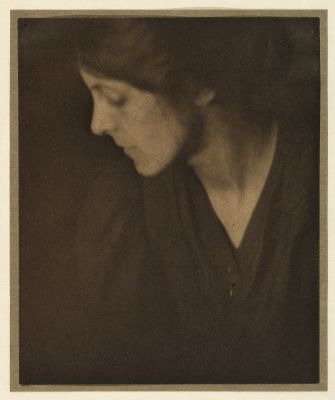

Title

The Bridge – IpswichArtist

Coburn, Alvin Langdon (American, 1882-1966)Key FigurePublication

Camera Work VIDate

1904Process

PhotogravureAtelier

Photochrome Engraving Company, New YorkImage Size

19.3 x 14.9 cm

The Bridge, Ipswich was taken in 1903 demonstrates Coburn’s assimilation of the formal principles of Japanese art by using notan. Throughout his photographic career, Coburn often strengthened the impact of this Japanese aesthetic by using a telephoto lens.

One of the most important and long-lasting influences on Coburn’s perception, his future life and his art was that of the teaching of artist, printmaker and arts educator Arthur Wesley Dow, whose Summer School of Art he attended in 1903. Set on the Ipswich River, Massachusetts, twenty-eight miles from Boston, in a house once owned by Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882), the school ran from 1891 to 1907. From 1895 to 1904, Dow taught at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, where his pupils included Kasebier and Max Weber, both of whom were relevant to Coburn’s artistic development—especially Weber, whom Coburn would not meet until 1910. From 1904 until his death, Dow was the director of the Fine Arts Department at Teachers’ College at Columbia University in New York, where he taught Georgia O’Keeffe. Influenced by the teachings of American professor of Oriental art Ernest Fenollosa (1853-1908) and inspired by the Japanese aesthetic for beauty and composition, Dow taught his students how to apply his art principles to painting, pottery, textiles, woodblock printing and photography, showing them how to transmute nature into tone and form. He sought the essence of reality rather than reality itself, encouraging simplicity and the paring down of detail to reach a perfect abstraction and balance. He stressed the importance of the “trinity of power”—line, notan (the juxtaposition and harmonization of light and dark tones; and color—in his 1899 publication Composition: a Series of Exercises in Art Structure for the use of Students and Teachers. Dow passed on to Coburn not only his fascination with the ink drawings of Japanese Zen Buddhist priest Sesshu Toyo (1420-1506), but also with the ukiyo-e woodblock prints of Ando Hiroshige (1797-1858) and Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849). Coburn would go on to collect original woodcuts and contemporary fine art prints of these and other Japanese artists’ work, now held in the Coburn Archives at George Eastman House. And it was also from Dow that Coburn learnt of mood created by light, especially twilight, and how to use notan so that light and dark tones suppressed detail and created a composition of overlapping abstracted shapes, avoiding the monotony or regularity and excessive repetition. These were lessons that Coburn learned well and which he consistently used in his photography. [1]

"a decidedly new note was struck by Alvin Langdon Coburn His ‘Ipswich Bridge’ presented a well-balanced composition and a rare feeling and understanding—most remarkable in so young a man, as he is only twenty [actually almost twenty-two] for lines, and special beauty." wrote Sadakichi Hartmann. Caffin also wrote of this same photograph that it was "strikingly handsome in composition, with a drowsy richness in the blacks and much tenderness in the scale of lights." Bridges would become a long standing metaphor in Coburn’s work. [2]

Reproduced / Exhibited

Frizot, Michael. New History of Photography. Place of publication not identified: Pajerski, 1999. Print P. 322

Hartmann, Sadakichi. Landscape and Figure Composition. New York: The Baker and Taylor Company, 1910. fig. 48

Kruse, Margret. Kunstphotographie Um 1900: D. Sammlung Ernst Juhl; Hamburg: Museum für Kunst u. Gewerbe, 1989 pl. 22

References

[1] Roberts, Pamela Glasson Coburn Alvin Langdon Pamela Glasson Roberts Fundación Mapfre and George Eastman House. 2014. Alvin Langdon Coburn. Madrid: Fundación Mapfre. pp. 20-21

[2] "Some Prints by Alvin Langdon Coburn," Camera Work, no. 6 (April 1904), pp. 18-19.