Title

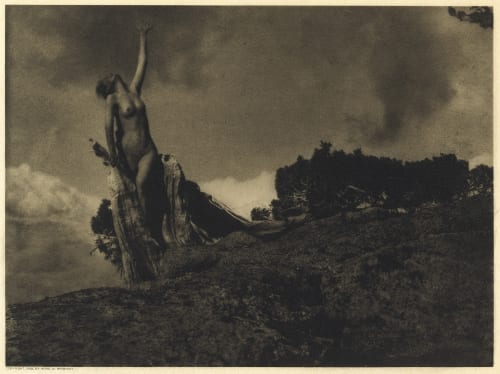

Soul of the Blasted PineArtist

Brigman, Annie A. (American, 1869-1950)Publication

Camera Work XXVDate

1909Process

PhotogravureAtelier

Manhattan Photogravure Company, NYImage Size

15.4 x 20.8 cm

In Soul of the Blasted Pine, taken in 1906, Brigman renders the nude woman rising from the tree stump with the same epic attitude as Eugène Delacroix’s Romantic masterpiece Liberty Leading the People (1830).

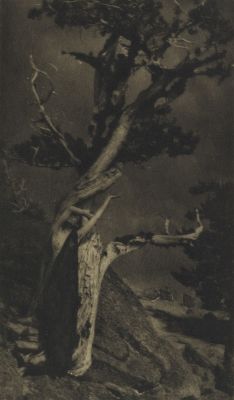

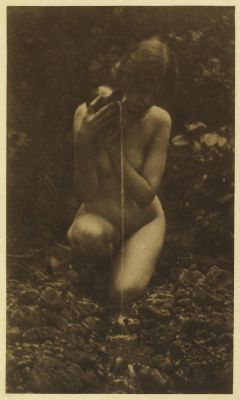

In Linda Nochlin’s famous 1971 piece “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists," she observes how there are no historical representations of artists drawing from the nude model which include women in any role but that of the nude model. Whereas it was acceptable for a man to study a nude woman as an object, a woman was forbidden to carry out such studies of either sex. In this regard alone, Anne Brigman’s photographs are remarkable. In the early 1900s, she produced self-portraits of her nude body, significantly scarred from an accident, often lodging herself within a gnarled juniper tree deep in the Sierra mountains. The major retrospective, Anne Brigman: A Visionary in Modern Photography at the Nevada Museum of Art, argues that at a time when Photo-Secession members dominated the conversation, Brigman illustrated the possibilities of a medium from a different perspective.

Armed with George Eastman’s new handheld Kodak camera that appealed to hobbyists with the slogan “You Press the Button, We Do the Rest,” Brigman would enlist her sisters as models or direct them when she was the actor. The bohemian atmosphere of the Bay Area, referred to as the “Athens of the West,” cultivated Brigman’s almost Pre-Raphaelite aesthetic which included props like bubbles, crowns, and capes — a dramatic departure from the mother with child images published by her predecessors such as Gertrude Käsebier.

By 1903 Alfred Stieglitz published Brigman’s work in Camera Work and awarded her membership to the Photo-Secession. Stieglitz looms large in Brigman’s legacy and in the exhibition. The prestige of Camera Work cannot be ignored at the turn of the century and his voice is ever present in their frequent correspondence. But during the war years, Stieglitz’s and Brigman’s paths divert. Brigman began repeating earlier works, such as the restaging of “Invictus” (1925), and Stieglitz declared her moment in photography was over. According to art historian Kathleen Pyne, Stieglitz went searching for another woman artist as muse and partner, which he found in the young painter Georgia O’Keeffe. It is clear that Brigman’s images left an impression on Stieglitz, such as in his photos of O’Keeffe posed as a “human tree,” as he puts it in a letter to Brigman. [1]

Reproduced / Exhibited

Kruse, Margret. Kunstphotographie Um 1900: D. Sammlung Ernst Juhl; Hamburg: Museum für Kunst u. Gewerbe, 1989 pl. 135

Weaver, Mike. The Photographic Art. Edinburgh, 1986. no. 67

Witkin, , London, and Shestack. The Photograph Collector’s Guide. London: Secker & Warburg, 1979. p. 105

References

[1] Kealey Boyd January 24, 2019 "Anne Brigman’s Radical Nude Self-Portraits from the Early 1900s" https://hyperallergic.com/481503/nne-brigman-a-visionary-in-modern-photography-at-the-nevada-museum-of-art/ cited 1/23

Anne Brigman: A Visionary in Modern Photography at the Nevada Museum of Art September 29, 2018 – January 27, 2019

Anne Brigman, a Pioneering Photographer of Nude Self-Portraits, Anya Ventura Dec 26, 2018 8:00 am