Title

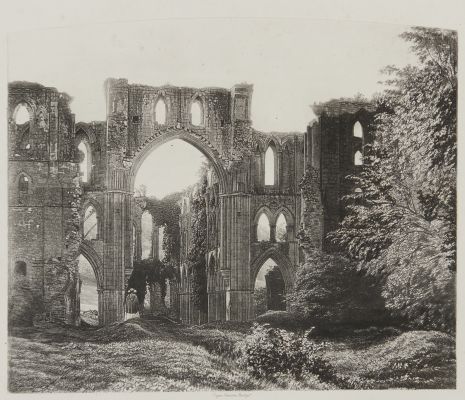

Rivaulx Abbey – The Choir of TranseptsArtist

Fenton, Roger (British, 1819-1869)Publication

Photographic Art TreasuresDate

1857Process

PhotogalvanographAtelier

Paul PretschImage Size

18.7 x 22.2 cmSheet Size

36 x 49 cm

From part III of Photographic Art Treasures

I dare say it is probably the first experiment in publishing an illustrated periodical devoted to the arts, executed in de luxe style with inserts produced by photographic printing plates. Joseph Eder [1]

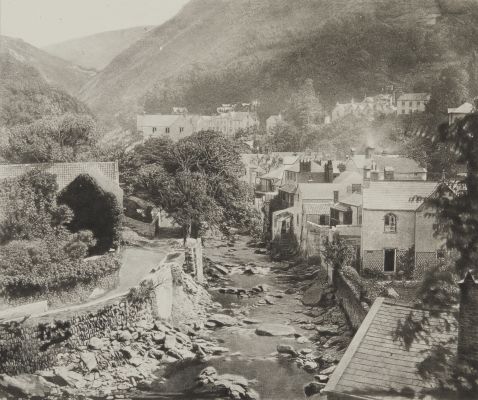

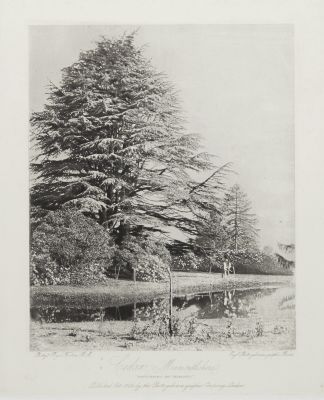

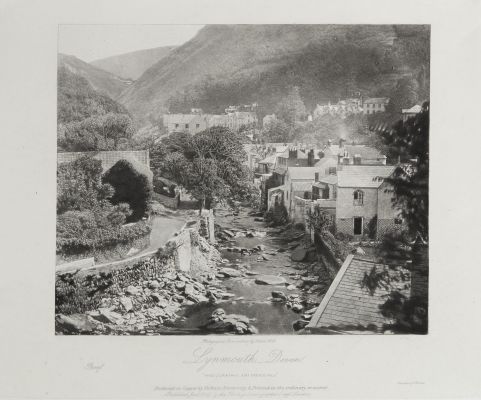

By the mid 1850s reproducing photographs in ink was primitive at best. Various attempts were being made but few were successful. In early 1856 Roger Fenton began to actively seek a more economical means of reproducing and circulating his photographs to a wider audience. He was impressed by Paul Pretsch’s "photogalvanographic" process which was a photomechanical means of reproducing photographs, drawings or paintings in ink printed on a press. Fenton and Pretsch joined forces in the Patent Photo-Galvanographic Company and launched the ambitious publication Photographic Art Treasures – the first periodical devoted to promote photography as art that was illustrated by photomechanical process. [2] The process was called Photogalvanography, which Pretsch patented in 1854. It was heralded in the British photographic press:

The first surprise on viewing these really lovely proofs is that of seeing a photograph in printer’s ink! — a real engraving in which houses and trees, and ruins, and water appear, not in the conventional guise in which we have been accustomed to see them, as reproduced by the pencil of the artist or the burin of the engraver, but in the beautiful truthfulness of Nature’s own touch. And how delightfully artistic is the rich dead black of the copper plate proof on India paper. What direct evidence is this of the absurdity of printing on a glazed surface. Let us now hear no more of photographic views on albumenized paper.

Pretsch’s photo-galvanographic process began with a photographically exposed dichromated-gelatine mould which was made to reticulate, from which he produced a copper intaglio plate by galvanoplasty. His halftone method was not entirely original. Others had developed methods of engraving from photographs. As early as the 1830s William Fox Talbot had patented a method of using "photographic screens or veils" in connection with a photographic intaglio process. However, Pretsch’s system achieved one thing that no others had previously managed— the inclusion of half-tones— the grays which make the photographic image unique.

Photographic Art Treasures illustrations were derived from works after photographs, mainly by Fenton, but also by other leading art photographers including William Lake Price and Robert Howlett. Pretsch’s plates could only handle a few hundred runs through the press before degrading. The degradation of the plate led Pretsch to divide and classify 500 impressions for Photographic Art Treasures based on their quality and sequence. “Choice proofs” and “proofs” were of the highest uniformity and quality, of the first hundred or so impressions to be pulled, while others were titled “prints.” [3]

Ultimately, some of the plates were enhanced with hand work which slowed the process of production so much so that each plate took about six weeks. Pretsch was also dogged by lawsuits from Fox Talbot who claimed that his Photoglyphic patents covered Pretsch’s inventions. Prices were high and demand low and the company folded in 1857 after issuing only five parts. In the end Pretsch proved the originality of his work and was awarded medals at the Great Exhibition of 1862, and was a finalist in the Duc de Luynes competition 1867. He did a great deal of work illustrating the Journal of the British Museum, but found it difficult to get on in London, and returned to Vienna a disappointed man, and died of cholera in 1873.

References

[1] Eder, Josef M. History of Photography p.32

[2] ibid p 582

[3] Gordon Baldwin, All the Mighty World: The Photographs of Roger Fenton, 1852-1860, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art; New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), 26.

Penrose’s Pictorial Annual 1911, p. 157, 161)

Paul William Morgan, "Paul Pretsch, Photogalvanography and Photographic Art Treasures" https://photogravure.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/PhotographicArtTreasures.pdf

Goldschmidt & Naef, The Truthful Lens (1980) No. 131.

Printing and the Mind of Man. Catalogue of the Exhibitions Held at the British Museum and at Earls Court, London [1963] No. 629

Helmut and Alison Gernsheim, The History of Photography 1685-1914, McGraw-Hill, New York, 1969, fig 102