Title

Rhinolophus HippocrepisArtist

Auer, Alois (Austrian, 1813-1869)Publication

FaustDate

1855Process

Nature PrintAtelier

Alois AuerImage Size

10 x 22 cmSheet Size

25.5 x 35 cm

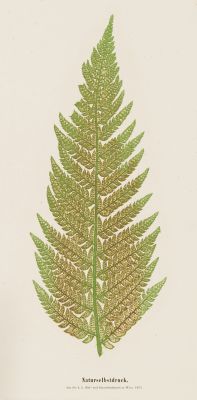

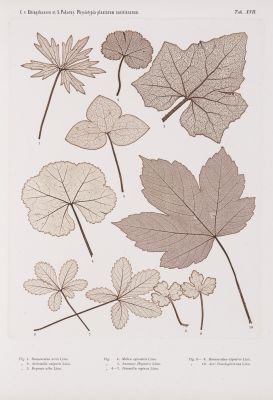

Here we find an extraordinary image of a bat – life size, wings extended, and highly mimetic. The large page is startling at first glance. Clearly a two-dimensional printed page, the image yet presents such fidelity to surface texture as to demand that viewers run their fingers over the creature’s furry body and leathery wings to verify its printedness. The texture conveying body and wings is about a millimeter thick on the surface of the paper, but this slight relief contributes surprisingly to the print’s verisimilitude. There is something wonderful about confirming that the bat is in fact printed.[1]

The fascinating nature print is from Alos Auer’s Faust: Poligrafisch-illustrirte Zeitschrift Für Kunst, Wissenschaft, Industrie Und Geselliges Leben (1854). In the mid-nineteenth century, technicians at the Austrian Royal and Imperial Court Printing Office devised the first method for mechanically reproducing nature prints: that is, prints from intaglio plates made from the impression of botanical specimens. Despite the complexity and apparent limitations of the process, Alois Auer, director of the printing office, boldly claimed that the new process was more important than photography. The ‘self-print of nature’, as Auer translates the term Naturselbstdruck, was his firm’s prize invention, garnering Austria a coveted medal at the 1851 Crystal Palace Exhibition in London. This was the only Council Medal, the highest honour, awarded for printing at the exhibition. The medal recognized the Austrians for their inventiveness with ‘all those new applications of art and science which dimly foreshadow an unknown future’. [2]

Nature printing is a printing process, developed in the 18th century, that uses the plants, animals, rocks and other natural subjects to produce an image. Originally nature prints were made by inking items such as fish or leaves with a roller, then printing them onto paper through a process of light controlled rubbing, much like one would print a woodcut. The “Auer Nature Print” however, began with an impression of the object into soft led which rendered a detailed continuous tone photographic likeness of an object without the use of a camera. It is likely that Walter Woodbury utilized a key concept inherent in this process as the basis for creating the popular Woodburytype. Alois Auer of Vienna invented the process in 1852, and Henry Bradbury patented his version of the process in England in 1853. Within ten years the technique was made obsolete by improvements in the photomechanical printing industry, and essentially “Nature Printing” disappeared from use.

Alois Auer named his process “Naturselbstdruckes”, which translates into “Nature-printing”, and then logically the end product of this process would be referred to as a “Nature Print”. However, the popular contemporary use of both of these terms confusingly refers both the original pre-1850’s process of “Nature Printing” and Auers’s. [3]

References

[1] Hume, Naomi, The Nature Print and Photography in the 1850s, The History of Photography Vol. 35 Number 1, Feb. 2011

[2] ibid

[3] Nicolai Klimaszewski https://www.alternativephotography.com/nature-printing/ Cited 1/23/23

DiNoto, Andrea, and David Winter. The Pressed Plant. New York: Stewart, Tabori & Chang, 2000.

Cave & Wakeman, Typographia Naturalis, 1967