Title

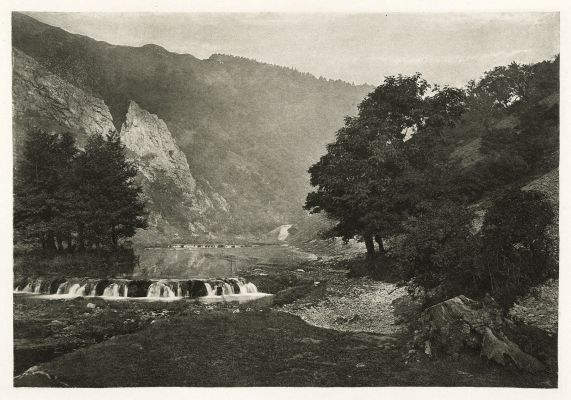

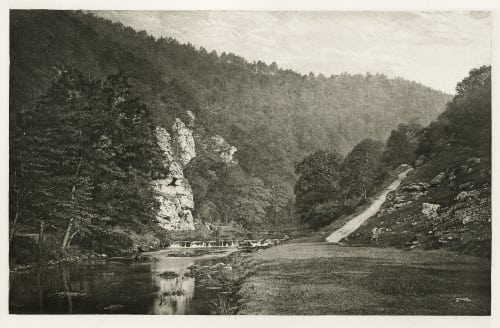

Plate XXXIX In Dove DaleArtist

Bankart, George (British, 1829-1916)Publication

The Compleat AnglerDate

1888Process

PhotogravureAtelier

Typo-Etching CompanyImage Size

13 x 20 cm

A treatise in two volumes on fishing. The photogravures from photographs taken in 1887 are primarily of river scenes, 27 of them are by Peter Henry Emerson and 25 by George Bankart. While Bankart’s images are sharp, deeply toned and printed in brown ink, Emerson’s are soft, delicate, and printed in a muted gray, qualities that add to their atmospheric presence. Emerson produced pale, low contrast images, stating in his subsequent book Naturalistic Photography (1889) that he preferred photogravure to every other photographic medium, including platinum printing. He found the process the only satisfying means of publishing his images because of the range of inks and papers available. By using his original negatives and closely supervising the printing of his photogravures, Emerson was the first to reveal the creative possibilities of the photogravure process.

A large Royal Quarto de-luxe edition with illustrations on India Paper was limited to 250 numbered copies. The Demy Quarto edition was limited to 500 numbered copies. This is a beautiful and under appreciated collection of Emerson’s atmospheric style predating Marsh Leaves by several years. According to Emerson, ‘the old and new style of photography can be nicely compared in this edition, the Derbyshire photographs being the work of an expert of the old "Sharp School". They are perfectly exquisite and refined examples of an appreciation of nature’s own glories and wonders.

Emerson’s photogravures represent one of the earliest applications of photogravure to pictorial expression in photography. Emerson is well known for his book Naturalistic Photography 1889 promoting his preference for the ‘optically softened’ image. In Naturalistic Photography he advocates for photogravure over other photographic media, including platinum prints believing nothing in nature has a hard outline, but everything is seen against something else, and its outlines fade gently into something else, often so subtly that you cannot quite distinguish where one ends and the other begins. In this mingled decision and indecision, this lost and found, lies all the charm and mystery of nature. He believed photogravure was the ideal medium to present pure photography because of its expressive potential including in addition to the ‘softening effect’, the flexibility of choice in ink and the range of available papers. At the time most photographers had tried to make sure that everything in their pictures was sharp.

From Crawford’s Keepers of Light: Most grain-gravure prints are not as sharp as actual photographs. Peter Henry Emerson admired this softened image, and he also liked the delicate tonal scale possible with gravure. He felt the technique was the photomechanical equivalent of the platinum print. Emerson started the idea, later popular among a number of photographers [Stieglitz, Camera Work] that gravures should be thought of as original prints and not merely as reproductions. Describing Emerson’s photographic illustrations, Nancy Newhall writes: They cast a spell over the book; they live in your mind as you read. Emerson’s preference for pale, low contrast, but fully toned images were reproduced with photogravure more and more successfully from one publication to the next.

The plates in The Compleat Angler were reproduced by the Typo-etching Company without any retouching.

References

Crawford, William. The Keepers of Light: A History & Working Guide to Early Photographic Processes. New York: Morgan & Morgan, 1979

Newhall, Nancy L. P.h. Emerson: The Fight for Photography As a Fine Art. New York: Aperture, 1978.

Emerson, P H. Naturalistic Photography for Students of the Art. Sampson Low & Co: London, 1889