Title

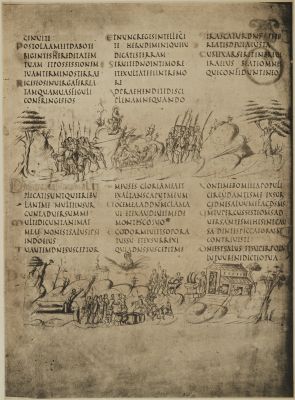

Plate IIIPublication

The Utrecht PsalterDate

1874Process

AutotypeAtelier

Spencer, Sawyer, and BirdImage Size

30.7 x 24.2Sheet Size

38.2 x 28 cm

This report is on The Utrecht Psalter, a illuminated manuscript, now held at Utrecht University in the Netherlands, settles some controversy as to its age. The Trustees of the British Museum had asked for a report from several distinguished scholars to resolve the matter. Included in the 1874 report are autotype reproductions of three pages from the original manuscript settling the controversy and highlighting a celebrated early use of photomechanical process in the dawn of the information age.

This autotype process was selected by those to whom it fell to direct the photographic reproduction of the Utrecht Psalter-a work then, and, as far as England is concerned, even now, without a parallel -not only on account of its plainly manifest advantages of cheapness, and its self-evident durability, but in no slight degree because also of the evenness and sameness of tones and qualitative depths obtaining throughout the whole of the impression; a result difficult, if not wholly impossible of acquisition in any other process whatever. The consequence is that we have today a facsimile of one of the most important and interesting manuscripts known to palæographical and theological enquirers, wherein is combined scrupulous adherence to the prototype with an endurance and cheapness contrasting favourably with the productions of every other competitive process. [1]

The Autotype Fine Art Company began life in 1868 as the Autotype Printing and Publishing Company, with a factory in Brixton and offices in London. From its inception to the present day the company has been involved in a variety of methods of producing images and imaging materials. For almost a hundred years, however, it was best known for its exploitation of Joseph Wilson Swan’s Carbon Process, a method of producing prints in permanent pigments. Swan patented his process in England in 1864 (No 503) and originally worked the process commercially himself. In 1868 he sold the English rights to a chemist, John Richard Johnson, and a photographer, Ernest Edwards, both of London. The same year, the rights were in turn acquired by the newly formed Autotype Printing and Publishing Company, with Johnson and Edwards becoming major shareholders. The name Autotype had been devised before the company existed, possibly as early as 1864. It was proposed by art critic and one time editor of Punch, Tom Taylor, and derived from two Greek words, ‘autos’ meaning self, and ‘tupos’ meaning stamp, as in the impress of a seal. The merits of the carbon process, rich tonal range and, particularly, its permanence soon commended itself to other photographic entrepreneurs. Almost immediately, rivals announced a series of doubtful ‘improvements’ to the process and the company was forced to assert its patent rights. The company successfully defended its position, either in court or by buying out the opposition. Under the company’s umbrella, Johnson was also working on improvements to Swan’s original process and new patents were filed in February 1869 and January 1870. Despite its early problems, the company successfully developed the business of supplying carbon printing materials as well as making carbon prints for the photographic trade and to sell directly to the public. In the early 1870s, the company underwent a period of rapid expansion and diversification. In 1871 a photo-collographic printing department was added to the Ealing factory under the management of J.R.M. Sawyer and W.S. Bird. It also acquired the expertise of J.A. Spencer by amalgamating with his independent carbon printing business. Other rival concerns were acquired in similar fashion, A further reorganization took place in 1873 when Spencer, Sawyer and Bird, purchased all patents, property and stock to form a new firrm, Spencer, Sawyer, Bird and Co. The Autotype Fine Art Company continued as a separate concern dealing with the fine art business until the end of 1875 when it was purchased by Spencer, Sawyer, Bird and Co. The new joint concern now became simply The Autotype Company. By the latter half of the 1870s, the Autotype Fine Art Company had become a prosperous and thriving concern with world wide interests. It was rapidly gaining a reputation for high quality carbon print reproductions of fine art and photographs. In the sixth edition of his manual, The Autotype Process (1877), Sawyer claims that the publication forms the basis of manuals in five languages and that galleries throughout Europe as well as “…our own splendid collections at the British and South Kensington Museums have yielded copies of their pictures.” Advertisements at the back of the book give further insights into the market for Autotype reproductions. The company’s catalogue included copies of works by Reynolds, Turner and Michael Angelo. Also listed is “A Splendid Series of Mrs Julia Cameron’s Art Photographs.” The body of the manual contains detailed instructions for working the Autotype process. There is also a note stating that instructions “will be given at the Autotype Works by previous appointment only, Tuesdays, Wednesdays and Thursdays in each week.” Towards the end of the century, Autotype broadened its interests further. It moved into the general photographic supply market, selling collodion for wet plates and later its own brand of gelatine dry plates. More importantly, it found a new market for the pigment paper. This was an essential component of photogravure, a new means of producing book and periodical illustrations that was being perfected and commercially exploited. The Autotype Fine Art Company was one of the first firms to experiment with the process and called their version ‘autogravure.’ They provided illustrations for books, including plates for Peter Henry Emerson’s Pictures of East Anglian Life, but soon found it more profitable to concentrate on supplying pigment paper to what was a rapidly growing branch of the printing industry. By 1930, production of photogravure pigment paper represented about 75% of the company’s manufacture. In 1919 Autotype purchased the rights to H.E. Farmer’s Carbro process, carbon prints made directly from bromide prints. Autotype simplified the process and began promoting it commercially in 1921. It became popular during the 1920s and 1930s, particularly in the form of trichrome carbro printing, a means of producing fine colour prints. [2]

References

[1] Birch Walter de Gray. The History Art and Palaeography of the Manuscript Styled the Utrecht Psalter. Samuel Bagster & Sons 1876. Intro

[2] Hannavy John. Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography. Routledge 2008. p 104, citing Brothers, A. Photography: Its History, Processes, Apparatus, and Materials, London, Charles Griffin and Company Limited, 1899. Burton, W. K. Practical Guide to Photographic and Photomechanical Printing, London, Marion and Company, 1887. Gernsheim, Helmut and Alison, The History of Photography, London, Thames and Hudson, 1969. Mitchell, K.J.M. The Rising Sun—The fi rst 100 years of the Autotype Fine Art Company (unpublished). Sawyer, J.R. The Autotype Process, London, Autotype Company, 1877 (sixth edition). Wakeman, Geoffrey, Victorian Book Illustration, Newton Abbot, David & Charles, 1973