Title

Plate 8Artist

Ulmann, Doris (American, 1882-1934)Publication

Roll Jordan RollDate

1933Process

PhotogravureImage Size

21 x 16 cm

One of the highlights of 20th century photography and photogravure.

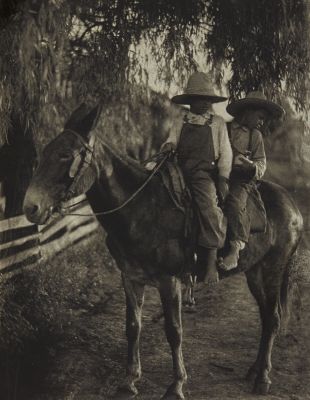

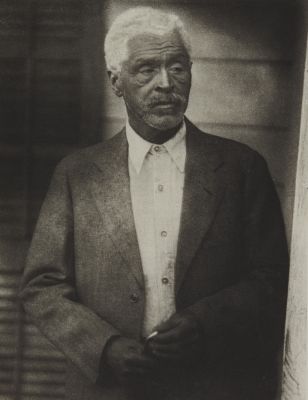

Beginning in 1929, Doris Ulmann, a graduate of the Clarence White School, undertook a project in the Gullah coastal region of South Carolina photographing former slaves and their descendants to illustrate Julia Peterkin’s Roll Jordan Roll. Reproduced as 90 lavish hand-pulled photogravures, Ulmann’s images and Peterkin’s text generated a body of work critically acclaimed as one of the first art books to portray African Americans as people rather than stereotypes and one of the finest, most renowned photogravure-illustrated books of the twentieth century. In Ulmann’s photographs, there is an atmosphere of love that seems to envelop her subjects. Her attitude toward people was reflected in her delicate use of natural light and the soft-focus lens. She was inspired by the simplicity of the Gullahs’ lifestyle—their inner strength, amid enormous difficulties, touched her deeply spiritual nature. [1]

Ulmann’s photographs have historically evaded categorization and Roll Jordan Roll is no exception—the work straddles a line between the pictorialist print aesthetic and the modernist compositional concerns, including a priority of form, sharp tonal contrast, quality of line, and un manipulated prints. Over the twenty years of her production, Ulmann’s work evolved from exhibiting typical features of pictorialism to a modernist compositional aesthetic, yet her continued use of photogravure in Roll Jordan Roll places her as a non-conformist holdout or visionary when it comes to the “perceptual experience mediated by technologies of light, vision, and reproduction” [2].

A trade edition was issued in a significantly smaller format and with fewer plates which were printed in half-tone. An extra signed photogravure plate was issued with the deluxe edition. Few copies of this deluxe edition had been distributed at the time of Ulmann’s death in 1934; most were donated by her heirs to the Tuskegee Institute to be sold for that school’s benefit.

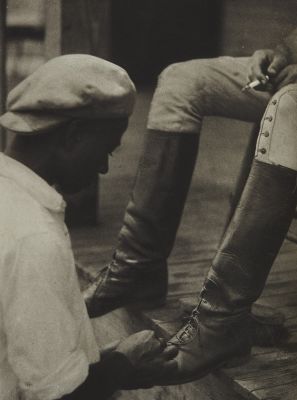

‘The Chain Gang’, one of a series of three images of southern African American prisoners published in Roll Jordan, Roll illustrates the racial penal system of the South-that an inordinate number of southern African American men experienced firsthand in the period Ulmann worked. And though the photographer attempted to create a certain symmetry and balance in this image, as in her other two published images of the chain gang, the different positions of the heads and bodies of the members of this group convey their independence, defiance, and longing for freedom. [3]

Reproduced / Exhibited

Gillespie, Sarah K. Vernacular Modernism: The Photography of Doris Ulmann, Athens, Georgia : Georgia Museum of Art, University of Georgia, 2018. pl. 75

Jacobs, Philip W. The Life and Photography of Doris Ulmann, Lexington The University Press of Kentucky, 2015. fig. 25 (platinum)

Ulmann, Doris, William Clift, and Robert Coles. The Darkness and the Light. Millerton, N.Y.: Aperture, 1974. p. 37.

References

[1] Ulmann, Doris, William Clift, and Robert Coles. The Darkness and the Light. Millerton, N.Y.: Aperture, 1974. p. 65.

[2] Lewis, Jacob W. Charles Negre in Pursuit of the Photographic. 2012. Print. Lambrechts, Eric, and Luc Salu. Photography and Literature: An International Bibliography of Monographs. London: Mansell, 1992. Print.

[3] Jacobs, P. W. (2001). The life and photography of Doris Ulmann. University Press of Kentucky. July 12, 2024

Michelle C. Lamunière (1997) “Roll, Jordan, Roll and the Gullah photographs of Doris Ulmann.” History of Photography 21:4, 294-302.