Title

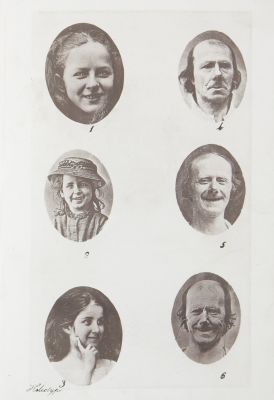

Pl. 1Artist

Rejlander, Oscar G. (British, 1870-1875)Publication

The Expression of the Emotions in Man and AnimalsDate

1872Process

HeliotypeAtelier

Ernest EdwardsImage Size

19 x 18 cm

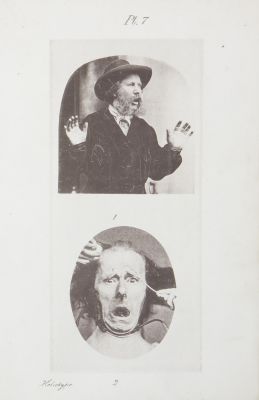

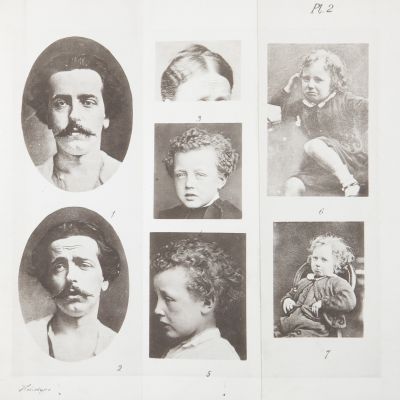

Photographic technology improved rapidly during the latter half of the 1800s. Once it became capable of taking pictures faster than what the naked eye could see, it began to affect measures of scientific integrity.[1] Darwin incorporated the photographic illustrations in this volume to support his key point that man’s facial muscles had evolved from the faces of monkeys, and were not divinely created as a unique means of self-expression. He commissioned Oscar Gustave Rejlander for some of the images, others he borrowed from Duchenne de Boulogne and from Herr Kinderman from Hamburg and Dr. Wallich. The plates were among the first successful published examples of heliotypes (collotypes) as invented by Ernst Edwards and a significant link in the evolution of visual culture at the intersection of art, science and psychology. Darwin’s concern was to show how human expressions link human movements with emotional states, and are genetically determined and derive from purposeful animal actions.[2]

Reproduced / Exhibited

Marien, Mary W. Photography: A Cultural History. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: SunSoft Press, 2002. fig. 3.28.

Charles Darwin, Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, John Murray, London, 1872, pl 6

Philip Prodger: Darwin’s Camera, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2009

Scenes in a Library, Carol Armstrong, The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA , 1998, fig 1.22

Helmut Gernsheim, The History of Photography, Oxford University Press, London, 1955, pl 124

Lucian Goldschmidt and Weston Naef, The Truthful Lense, The Grolier Club, New York, 1980, pg 66

Lori Pauli, Oscar G. Rejlander, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, 2018, pg 299

References

[1] Philip Prodger: Darwin’s Camera, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2009 How Darwin’s Photographic Studies of Human Emotions Changed Visual Culture https://www.themarginalian.org/2011/11/11/darwins-camera/

[2] Goldschmidt Lucien Weston J Naef and Grolier Club. 1980. The Truthful Lens : A Survey of the Photographically Illustrated Book 1844-1914. 1st ed. New York: Grolier Club