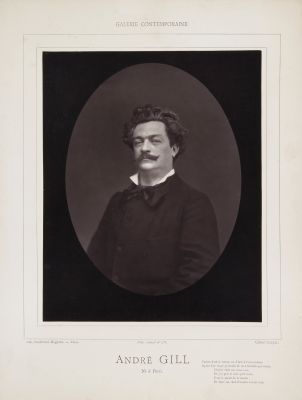

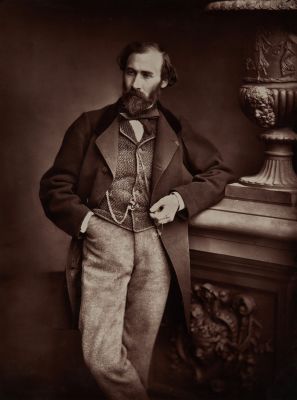

Title

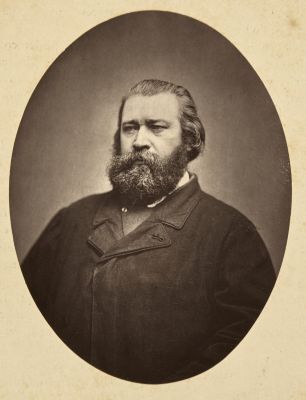

Pierre DupontArtist

Carjat, Etienne (French, 1828-1906)Publication

Galerie ContemporaineDate

1875 caProcess

WoodburytypeAtelier

Goupil & CieImage Size

22.2 x 18.2 cmSheet Size

35 x 26 cm

Born in Lyon on 23 April 1821, Pierre Dupont was the son of a blacksmith and endured the early loss of his mother, after which he was raised by his godfather, a village priest. Educated at the seminary of L’Argentière and later apprenticed to a notary, he found his way to Paris around 1839. There, his poems appeared in publications like Gazette de France and La Quotidienne, leading to his first volume Les Deux Anges in 1841. In 1842 he earned an Academy prize and began work on the official French dictionary. Soon his career turned toward songwriting—he composed both lyrics and melodies (often simultaneously) despite having no formal musical training, even employing Ernest Reyer to transcribe his airs. His powerful peasant and worker songs—such as Le Chant des ouvriers (1846) and Le Chant du pain—gained immense popularity, though Le Chant du pain was banned and the outspoken Chant des ouvriers contributed to his being sentenced in 1851 to seven years of exile (a sentence later annulled). He spent his later years back in Lyon, where he died on 25 July 1870. His enduring works include collections like Chants et chansons (three volumes, 1852–1854) and Chants et poésies (7th edition, 1862), featuring beloved songs such as Le Braconnier, Le Tisserand, La Vache blanche, and La Chanson du blé.

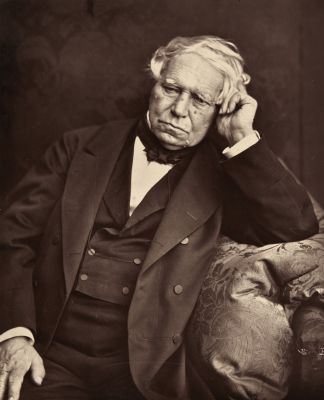

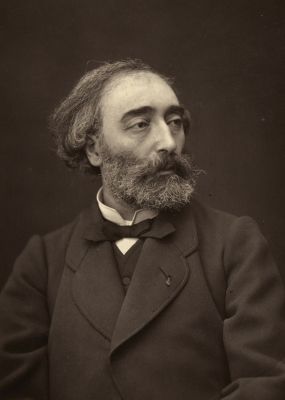

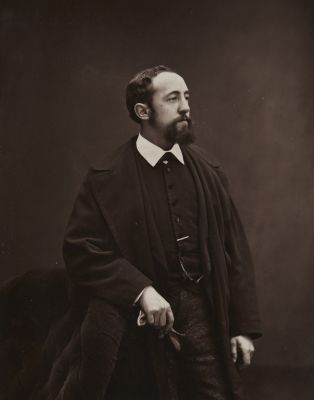

Issued in installments by the Parisian publisher Goupil between 1876 and 1884, the Galerie Contemporaine, Littéraire, Artistique brought together 241 portraits of prominent figures in literature, music, science, and politics offring the French public an unprecedented visual gallery of the people shaping their cultural and civic life during the Second Empire and the early Third Republic.

The project was fueled by a spirit of national pride and by a new, more modern fascination with fame. Its subtitle—Littéraire Artistique—signaled a desire to elevate photography as a vehicle for high culture, while also capitalizing on the growing appetite for celebrity portraiture.

The images themselves were printed as woodburytypes giving the portraits a richness and permanence that aligned perfectly with the project’s lofty cultural ambitions.

Today, Galerie Contemporaine endures not only as a milestone in the history of photography and publishing, but also as a vivid record of the artists, scientists, and statesmen whose lives and ideas defined modern France.