Title

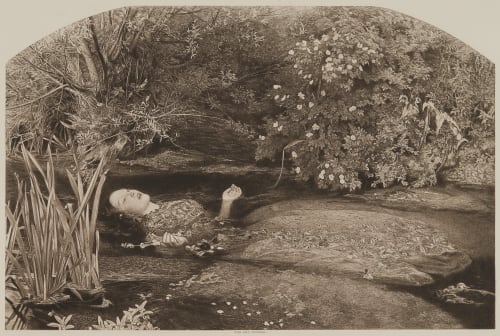

OpheliaArtist

Millais, John Everet (English, 1829-1896)Publication

The Art JournalDate

1852Process

PhotogravureImage Size

26 x 17 cm

This scene depicted is from Shakespeare’s Hamlet, Act IV, Scene vii, in which Ophelia, driven out of her mind when her father is murdered by her lover Hamlet, falls into a stream and drowns. Shakespeare was a favorite source for Pre-Raphaelite painters, and the tragic-romantic figure of Ophelia from Hamlet was an especially popular subject. Pre-Raphaelite paintings were characterized by high detail, close attention to nature, abundant color, and non-simplistic composition, with subjects frequently stemming from the Romantic, the medieval, and the literary.

The most renown painting of Ophelia was by English painter John Everett Millais (1851) reproduced here by photogravure.

In 1861 Henry Peach Robinson made an ‘Ophelia’ photographically – titling it ‘The Lady of Shalott’ and linking it to Tennyson’s, The Lady of Shalott, first published in 1832. The Lady of Shalott tells of a woman who suffers under an undisclosed curse. She lives isolated in a tower on an island called Shalott, on a river which flows down from King Arthur’s castle at Camelot. Not daring to look upon reality, she is allowed to see the outside world only through its reflection in a mirror. One day she glimpses the reflected image of the handsome knight Lancelot, and cannot resist looking at him directly. The mirror cracks from side to side, and she feels the curse come upon her. The punishment that follows results in her drifting in her boat downstream to Camelot ‘singing her last song’, but dying before she reaches there.

The Lady of Shalott by Robinson was the first photograph to illustrate the work of Tennyson, and as he stated, he believed that he followed Pre-Raphaelite principles in doing so. I made a barge, crimped the model’s hair, PR fashion, laid her on the boat in the river among the water lilies, and gave her a background of weeping willows, taken in the rain so that they might look dreary. [1]

Robinson’s Lady of Shalott is practically a photographic copy of Millais’ Ophelia, even having been cropped to mimic the arched shape of Millais’ canvas.

A play, a painting, a photograph, a poem and a photogravure considered together offer a compelling perspective on the blurred lines between painting, photography, reproduction and art in the 19th century.

References

[1] Masterpieces of Victorian Photography, 21