Title

On the Cliff Walk, NewportArtist

Coburn, Alvin Langdon (American, 1882-1966)Key FigurePublication

The Novels and Tales of Henry JamesDate

1907Process

PhotogravureImage Size

10.7 x 8.2 cm

This might be the greatest series of frontispieces ever created.

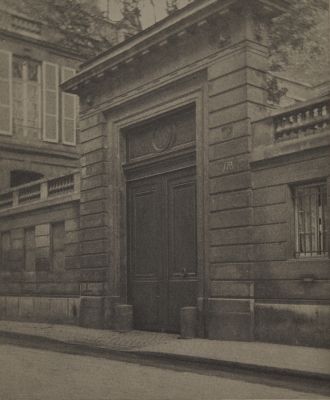

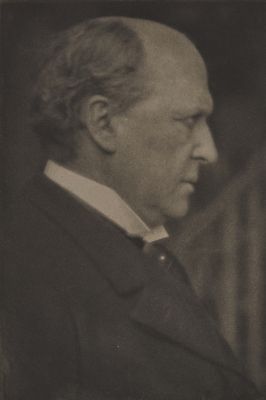

Henry James had a general disregard both for illustrations of his prose and for photography… he believed that illustrations should not be asked to perform the descriptive work of the writer, that they undercut the efficacy of literature, and that using the visual in support of the verbal pandered to a more popular audience. Beyond his disdain for illustration, James’s particular dislike for photography was based on his belief that photographers lacked craft and genius and that photography was more mechanical than artistic… And yet he not only chose Coburn’s photogravures as illustrations for the monument to his life’s work but also assisted and directed the photographer in imagining and selecting scenes for inclusion. James first met the Coburn in New York City in 1905, during the author’s belated return to the United States, where he was engaged on a lecture tour and, not incidentally, trying to work out the details for publishing the New York Edition of his Novels and Tales. Since James’s return to America (after an absence of more than twenty years) was newsworthy, the Century Magazine sent Coburn to photograph the novelist. The result of that first encounter was not published, but James was sufficiently impressed by Coburn to invite him to Rye the following year, where images were taken that James would gladly employ in the New York Edition: a side profile of the author was used for the first volume in the series, Roderick Hudson, and another of the main entrance to Lamb House graced volume IX as “Mr. Longdon’s” for The Awkward Age. By a happy coincidence, even as Coburn was making prints of these early images, Charles Scribner’s Sons raised the question of illustration with James for the New York Edition. James had long been skeptical about the conjunction of picture and text (frequently voicing his disgust with the illustrated magazines upon whose patronage he was nevertheless dependent). Not surprisingly, then, initially he recoiled “with terror from the enterprise of first finding and then causing to be consummately captured” the twenty-plus subjects needed. If Scribners “could get one really artistic and charming figure-piece for each book, I would resign myself,” James confessed; “but it’s not for me to say whom they can get it from—in any form above the mere usual magazine average, or even maximum: which wouldn’t be good enough.” Considerably reanimated by his agent’s encouragement, however, James came to accept the challenge of securing appropriate frontispieces for the Edition. In short order, he eagerly began collaborating with Coburn (serendipitously at hand), providing the photographer with detailed instructions for securing just the right images—in London, in Paris, in Rome, in Venice—to embellish his series of volumes.

James famously called photography the “hideous inexpressiveness of a mechanical medium.” He told his publishers at Scribner’s that he wanted only a single good plate in each volume of the New York edition. “Only one but of thoroughly fine quality.” George Bernard Shaw called Coburn “the greatest photographer in the world.” Alfred Stieglitz wrote that “Coburn has been a favored child throughout his career… No other photographer has been so extensively exploited nor so generally eulogized,” but that didn’t stop him from giving the young artist two solo exhibitions at 291.

References

Adams, Timothy Dow. "Material James and James’s Material: Coburn’s Frontispieces to the New York Edition." The Henry James Review, vol. 21 no. 3, 2000, p. 253-260