Title

NégresseArtist

Benoist, Marie-Guillemine (French, 1768-1826)Publication

Galerie Du LuxembourgDate

1828Process

EngravingImage Size

19.9 x 16 cmSheet Size

52 x 34 cm

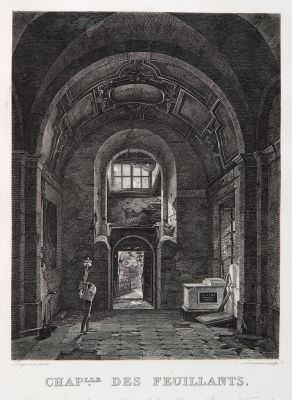

This beautiful engraving of Benoist’s famous painting appeared in the Galerie Du Luxembourg in 1828. The publication was advertised as a collection of plates engraved by our young Artists which proves how much the art of Engraving has made progress in France. Also included in this volume is an engraving after Daguerre’s painting, Chapelle des Feuillants (1814) by Augustin-Francois Lemaître. Together the works offer a perspective of the state of the art of engraving in the decade before the announcement of the invention of the daguerreotype.

Marie-Guillemine Laville-Leroulx (Benoist was her married name) was born into a middle-class family. Her father was a civil servant who had failed in business. He believed firmly that his two daughters should be educated to earn their own way—an unusual attitude in the eighteenth century. Marie-Guillemine and her sister first studied painting with Vigée Le Brun and later were among three women whom David took into his studio in the Louvre, challenging concerns about propriety raised by the government minister in charge of the palace.

Laville-Leroulx made her debut at the Salon of 1791, when the revolutionary government opened the exhibition to all artists for the first time. She was ambitious, exhibiting history paintings, which were widely considered beyond women’s capacities. She listed herself as a student of David, even though the artist was a firm supporter of the Revolution, while her family remained loyal to the king. Two years later, she married Pierre Vincent Benoist, who was, like her family, a monarchist. During the Reign of Terror the couple’s life was difficult. By 1800, however, Napoleon I had staged a coup d’etat and installed himself as First Consul of the Directory. With the change in government, Mme Benoist, as she was now known, was ready to take up her public career as an artist. In choosing to paint a woman of color, Benoist selected an unusual subject for a portrait and engaged a politically contentious issue. The only other likeness of an African to be exhibited at the Salon during these years was Anne-Louis Girodet’s Portrait of Citizen Jean-Baptiste Belley, Ex-Representative of the Colonies. Girodet, like Benoist, was a student of David. Belley, who was born in Senegal and enslaved in the French colony of Saint-Domingue, had been freed because of his military service in the French army and was elected one of the colony’s three representatives to the French revolutionary government. Serving from 1793 to 1797, he became well-known as an advocate for racial equality. Girodet’s painting, which juxtaposes Belley’s head with a marble bust of the abolitionist philosopher Guillaume-Thomas Raynal, was understood by visitors to the Salon in 1798 as an argument for emancipation.

Two years later, however, Napoleon I was consolidating his power and began to lay the groundwork for reviving the institution of slavery. He recognized that the Revolutionary government’s decision to free slaves in French territories had not only antagonized citizens of these colonies and other nations, but also had jeopardized the immense profits from the cultivation of sugar that were important to France’s economy. His move was contentious, but it was supported by many who had a vested interest in the economics of slavery, including Benoist’s husband. [1]

References

[1] Dr. Susan Waller https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/renaissance-reformation/rococo-neoclassicism/neo-classicism/a/marie-guillemine-benoist-portrait-of-a-black-woman cited 02/23/23