Title

Maison Elevée rue St. Georges par M. RenaudArtist

Fizeau, Louis Armand Hippolyte (French, 1819-1896)Key FigurePublication

Excursions DaguerriennesDate

1843 caProcess

Photogravure (Fizeau process)Atelier

Goupil et VibertImage Size

14.3 × 19.4 cmSheet Size

29 × 38 cm

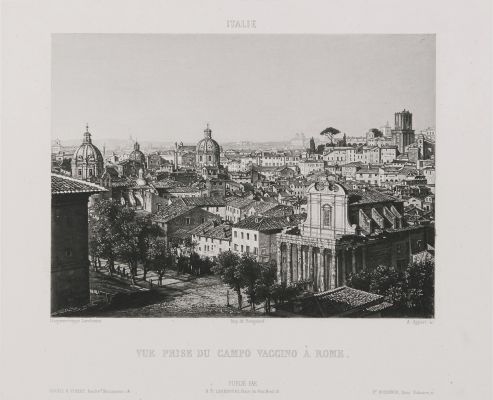

We do not know in Paris of a roof as rich as the one which crowns this small hotel. The slates are adjusted tees by regular compartments which form scales, octagons and diamonds. A gracious antefix cut was to complete this roof, and unfortunately was not executed. If the reader sees it on the engraving, is that the Daguerrian proof was taken from the drawings that the architect had exhibited at the Louvre, and that the proof daguerrienne itself has been transformed into a plate, engraved according to the admirable process of M. Fizeau. Maison élevée rue St George par M. Renaud, a plate that was added in only a few special editions of the second series, between plates 33 and 34, but not included in the index of the volume and realized, as Henry Berthoud explains in the accompanying text, from a daguerreotype that was not directly taken of the building but of the drawing that the architect had exhibited at the Louvre.

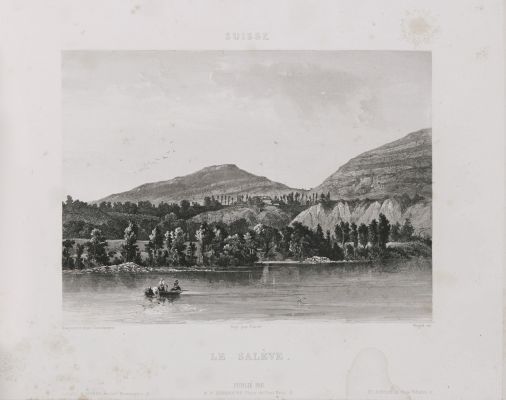

In 1839, within just a few weeks of the public announcement of the invention of the daguerreotype, budding daguerreotypists had learned the technique and set off to try their luck in far-flung destinations across Europe, Africa and the Near East. Where they succeeded, they produced the first photographic images ever made of these regions and inaugurated a practice which would forever alter the experience of travel. Parisian optician, maker of scientific instruments and entrepreneur Noël-Paymal Lerebours gathered together over a hundred of these daguerreotypes, had them traced and translated into engravings and published them. The resulting Excursions daguerriennes: Vues et monuments les plus remarquables du globe was the first book to be illustrated from photographs. While most were copied by the hand of an artist, three were printed directly from etched daguerreotype plates making Excursions Daguerriennes a monument in the history of photomechanical printing. The 1842 edition marks the first publication of prints made by a complex process of electroetching invented by Hippolyte Fizeau in which the daguerreotype itself became the printing plate. These prints mark the first appearance in book form of illustrations created by a photo-mechanical process. [1]

The dates of publication of Excursions daguerriennes is often confused. At least five different covers and title pages exist, dated 1840, 1841, 1842 and 1844. References in various French periodicals allow the publication history of the work at least partially to be reconstructed. Excursions daguerriennes began publication in issues of four plates. The first issue was released on 1 August 1840, with the total projected plates planned at 50. Fourteen issues followed, with the 10th released by 10 September 1841 and the 15th by 12 December 1841. These constitute the “First Series” of 15 parts and what turned out to be 60 plates, rather than 50 (a fact reflected in the dropping of the phrase “Collection de 50 Planches” from the titlepages of the issues). In the two-volume bound set of plates, which is the form the work is usually found in libraries, these make up the first volume. On 14 May 1842 a second series of plates was announced as the “Nouvelles Excursions Daguerriennes”. The 13th and last issue of the second series was released on 20 Dec 1844, with the complete set announced as “114 plates” shortly afterwards. The second series plates usually make up the second volume of the bound set, although somewhat confusingly this often contains only 53 plates (not the required 54), of which only 51 are numbered. To add to the confusion, on 1 Jan 1844 various additional selections of plates had been released, including “Sites et monuments de France”, “Sites et monuments d’Italie” and “Petit Album de Choix”. Whether these were merely duplicates from the existing published editions or were additions to the editions to increase the total number of plates is unclear. [2]

Reproduced / Exhibited

Leonardi, Nicoletta and Natale, Simone. Photography and Other Media in the Nineteenth Century, Pennsylvania State University Press, 2018

p. 128

Crawford, William. The Keepers of Light: A History & Working Guide to Early Photographic Processes. New York: Morgan & Morgan, 1979. p. 239

Metropolitan Museum collection

George Eastman House collection

Reijksmuseum collection

New York Public Library (has a proof state and a final state) collection

References

[1] Foster, Sheila J. Imagining Paradise: The Richard and Ronay Menschel Library at George Eastman House, Rochester. Rochester, NY: George Eastman House, 2007. Print.

[2] Hudson, Giles https://mattersphotographical.wordpress.com/2018/11/24/excursions-daguerriennes/. cited 2/15/23

Buerger, Janet E. French Daguerreotypes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989. no. 58.

Howe, Kathleen S. Intersections: Lithography, Photography, and the Traditions of Printmaking. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1998.

Marien, Mary W. Photography: A Cultural History. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: SunSoft Press, 2002.

Crawford, William. The Keepers of Light: A History & Working Guide to Early Photographic Processes. New York: Morgan & Morgan, 1979. p. 239

Luke Gartlan, "Inventing Provinciality: St Andrews and the Global Networks of Early Victorian Photography", British Art Studies, Issue 23, https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-23/lgartlan

The Photograph in Print, Multiplication and Stability of the Image by Sylvie Aubenas, Frizot, Michel. A New History of Photography. 1999.

Steffen Siegel, “Uniqueness Multiplied: The Daguerreotype and the Visual Economy of the Graphic Arts,” in Leonardi and Natale, eds., Photography and Other Media in the Nineteenth Century (University Park, P.A.: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2018), 116–30.