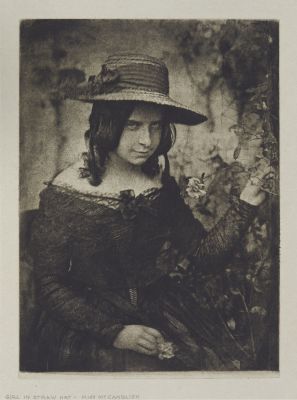

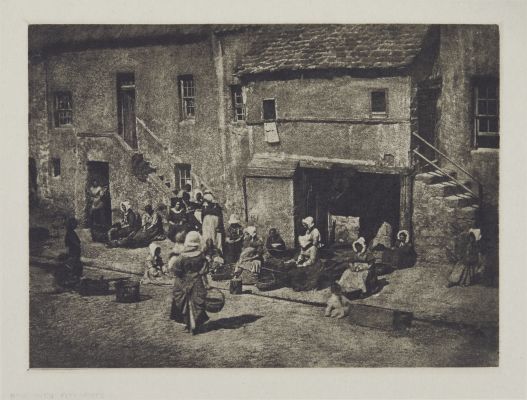

Title

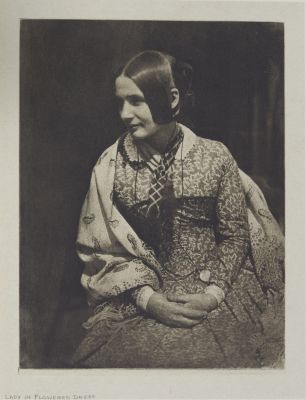

Lady RuthvenArtists

Hill, David Octavious (Scottish, 1802-1870)Adamson, Robert (Scottish, 1821-1848)Publication

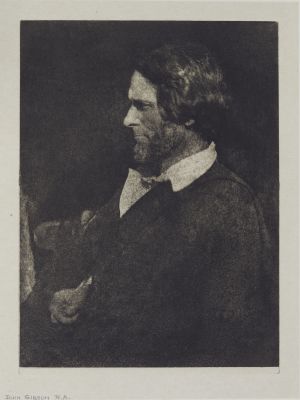

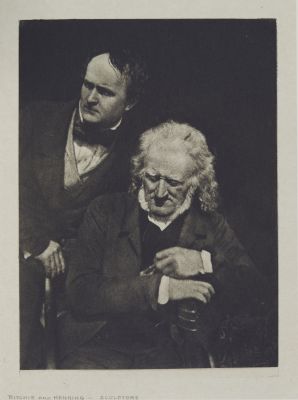

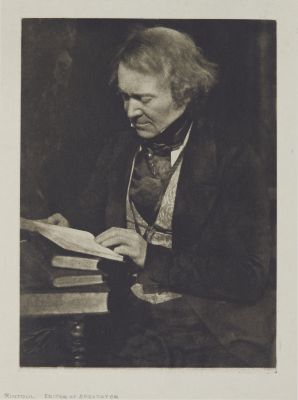

Twenty photogravure prints by James Craig AnnanDate

1890 plate (1843-1847 negative)Process

Photogravure (tissue)Atelier

James Craig AnnanImage Size

14 x 19.2 cm

…so completely had [Hill’s] very existence been forgotten that on his death in 1870 not a single photographic journal even mentioned the fact. J. Dudley Johnston

It is impossible to estimate what impact James Craig Annan would have on the future of photography when he began experimenting with using photogravure to print Hill and Adamson’s calotypes in the 1890s. The documentation of this work is thin. We know that Around 1880, Andrew Elliot commissioned Thomas Annan’s firm (T&R Annan) to make carbon prints from Hill’s paper negatives for public sale. And we know that Thomas and James Craig learned the photogravure process from Klic in 1883, only four years after it was invented. So it makes sense that, after learning the process, James Craig believed that photogravure could be a more accurate interpretation of the Hill and Adamson material than his father’s carbon prints. The surface quality alone was enough. Like photogravure, calotypes and salt prints have a soft mat surface.

Despite commercial restrictions limited by the firm’s contract with Elliot (which took nearly 50 years to finally complete), James Craig began to experiment with Hill’s negatives in photogravure. A highly skilled technician, Annan was fastidious, in part because he was a perfectionist and also because he may have felt a personal responsibility to Hill. Hill was a family friend and is known to have influenced Annan’s pursuit of art. The exact details and timing of Annan’s efforts are unfortunately lacking. What is known is that Annan eventually produced an uneditioned folio of 20 Hill and Adamson images.

Over the years Annan lent Hill and Adamson photogravure prints to exhibitions in Europe and America: to Hamburg in 1893 and 1899; to Glasgow in 1901; to the Scottish Photographic Federation in Perth in 1904; to the ‘291’ Gallery in New York in 1906; to the Salon in London in 1909; and to Buffalo in 1910. And by sending the prints to Stieglitz for Camera Work in 1905, 1909 and 1912 Annan ultimately brought Hill and Adamson back into the public eye.

On August 2 August, 1945 James Craig Annan wrote to Gersheim relating parts of the story… I made the photogravure reproductions for my own satisfaction as I thought I could get more artistic results than the carbon prints our firm made in 1879-81 for Andrew Elliot’s projected volume which as you are aware was not issued until 1928. Having been paid by Elliot for making the prints for this volume I could not decently issue my prints until his volume was given to the public. Except for showing them to friends nothing was done until Stieglitz asked to have some of [them] for “Camera Work” and small groups of them were printed and issued in several numbers early in this century. In addition a few prints of the 20 plates were made and in a loose folder were sold to friends and admirers. These, still in deference to Elliot’s publication, were never advertised. I find there is one complete set remaining at Sauchiehall St. and if you care to have it the cost will be Five Guineas. I did not collaborate with anyone else in the production. There is no letterpress. The plates are probably still in good condition and further copies might be printed if – and when – the fine Japanese paper used again becomes available.

References

[1] Hans P. Kraus Jr (Firm) Schaaf LJ. Sun Pictures. Catalog Eleven St. Andrews and Early Scottish Photography Including Hill & Adamson. New York: H.P. Kraus Jr. Fine Photographs; 2002.

[2] Annan letters to Gernsheim 31 March 1945 held at the Harry Ransom Center, Transcribed SS 2015