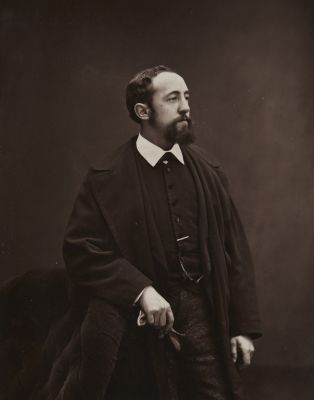

Title

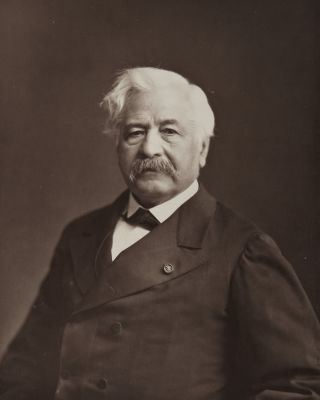

Jean-François MilletArtist

UnknownPublication

Galerie ContemporaineDate

1875 caProcess

WoodburytypeAtelier

Goupil & CieImage Size

10 x 7.5 cmSheet Size

35 x 26 cm

Born in the Normandy village of Gruchy, Jean-François Millet emerged as one of the most influential painters of 19th-century France and a central figure of the Barbizon school. Trained at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, Millet turned away from academic history painting to focus on the lives of peasants and agricultural laborers. His canvases—most famously The Gleaners (1857) and The Angelus (1857–59)—portray rural toil with a gravity and reverence once reserved for biblical or classical subjects. To many contemporaries, this elevation of humble work was radical, even controversial, but to others it was a moving recognition of the dignity and endurance of the rural poor.

Millet’s deep respect for agrarian labor resonated far beyond painting. In Britain, the pioneering photographer Peter Henry Emerson (1856–1936) found inspiration in Millet’s vision. Emerson rejected the artificial staging of earlier studio photography, arguing that photographs should capture rural life with the same unvarnished naturalism that Millet had brought to canvas. His influential treatise Naturalistic Photography for Students of the Art (1889) explicitly cited Millet as a model, praising the painter’s ability to convey truth and poetry in scenes of ordinary work. Emerson’s photographs of fenland farmers, reed-cutters, and country children translated Millet’s themes into a new medium, helping to shape photography’s claim as a fine art rather than mere mechanical reproduction.

For Millet, the field was a stage on which universal human struggles—labor, faith, fatigue, and resilience—were enacted. His paintings, suffused with golden light yet unflinching in their realism, bridged the academic and the modern, speaking both to contemporary debates about social justice and to later artists such as Vincent van Gogh.

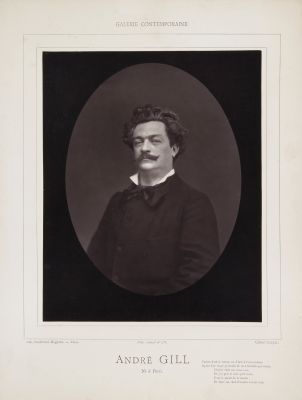

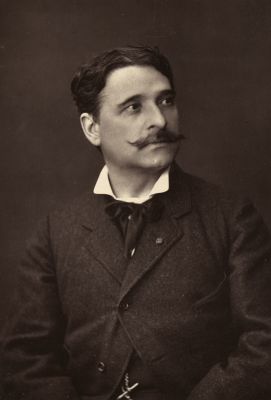

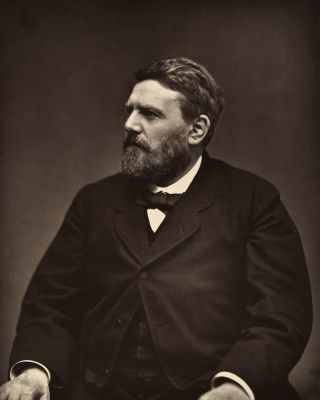

Issued in installments by the Parisian publisher Goupil between 1876 and 1884, the Galerie Contemporaine, Littéraire, Artistique brought together 241 portraits of prominent figures in literature, music, science, and politics offring the French public an unprecedented visual gallery of the people shaping their cultural and civic life during the Second Empire and the early Third Republic.

The project was fueled by a spirit of national pride and by a new, more modern fascination with fame. Its subtitle—Littéraire Artistique—signaled a desire to elevate photography as a vehicle for high culture, while also capitalizing on the growing appetite for celebrity portraiture.

The images themselves were printed as woodburytypes giving the portraits a richness and permanence that aligned perfectly with the project’s lofty cultural ambitions.

Today, Galerie Contemporaine endures not only as a milestone in the history of photography and publishing, but also as a vivid record of the artists, scientists, and statesmen whose lives and ideas defined modern France.