Title

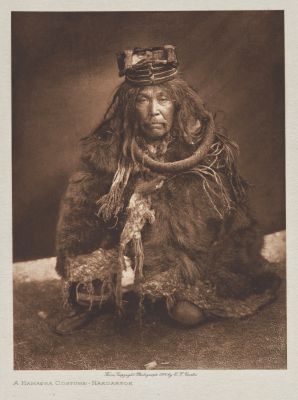

Horse Capture – Atsina pl 332Artist

Curtis, Edward Sherrif (American, 1868-1952)Key FigurePublication

The North American IndianDate

1908Process

PhotogravureAtelier

John Andrew and Sons, BostonImage Size

40 x 28 cm

Curtis wrote about Horse Capture: Born near Milk River in 1858. When about fifteen years of age he went with a war-party against the Piegan, but achieved no honor. From their camp at Beaver creek the Atsina sent out a war-party which came upon two Sioux. Remaining hidden in a coulee, the warriors sent an old man out as a decoy. When the Sioux charged him, the rest of the Atsina rushed out and killed them both. During the fight Horse Capture ran up to one of the enemy, who was wounded, in order to count coup, when one of his companions dashed in a head of him and was killed by the wounded Sioux. Horse Capture than counted first coup on the enemy and killed him. He married at the age of twenty-five. His great grandson, George Horse Capture, was the first Native American to be employed at the Smithsonian Institution in an executive capacity and was outspoken champion of Curtis’ photographs.

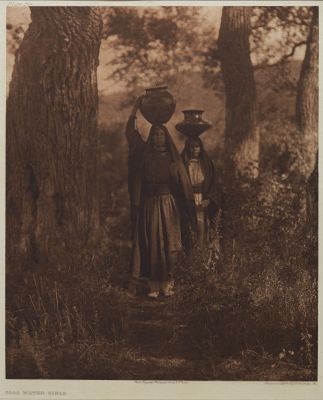

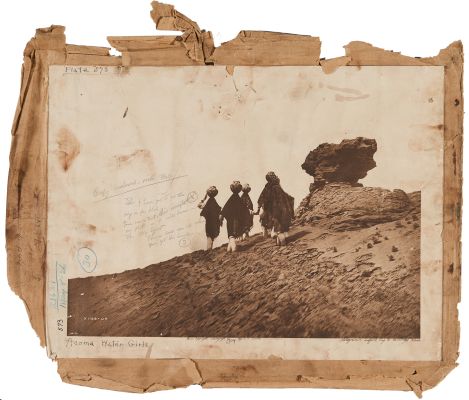

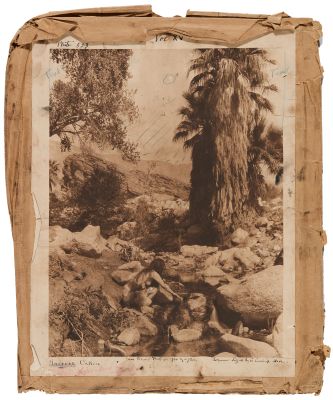

The North American Indian is one of the most significant and controversial representations of the Native American lifestyle ever produced. To this day it continues to exert a major influence on the image of Native American Indians in popular culture. Published in 20 volumes from 1907 to 1930, each exhaustive set includes more than 2,200 photogravures, in both small and large formats. Curtis methodically documented more than 75 tribes across the country. He was acutely aware of the changes occurring in Native American culture and tended to idealize his subjects. Curtis sometimes altered hairstyles and costumes and was known to have removed evidence of modern life from his compositions. His finished photogravures were romantically printed many in the closed, muted tones of pictorialism. William Crawford points out, in The Keepers of Light, that this soft, fine art effect, unfortunately ran counter to Curtis’s documentary intentions. Three types of paper were used Japanese Vellum, Dutch “Van Gelder,” and Japanese “Tissue,” also known as India Proof Paper. The tissue gravures are considered most rare because they are delicate and only thirty to forty sets were produced, with the remainder divided between Van Gelder and Vellum (resulting in about 166 sets each). Because of the scarcity of prints on tissue, as well as their outstanding registration, they usually command a higher price (the subscription records indicate that Curtis charged a 30% premium to subscribers ordering tissue editions).

Since the late 1970’s, after Curtis’ original copper plates were rediscovered, a few companies produced limited numbers of "restrikes" from the original plates. Unlike lithographs, these are true photogravures (although not vintage), generally printed on fine "art" papers. So, identifying original Curtis images comes down to discriminating between "vintage" gravures (defined as any plate from the original run, printed for inclusion in the subscription volumes of "The North American Indian") from more recent "restrikes" (defined as any photogravure that was reproduced after "The North American Indian" was originally published). While restrikes are not "authentic" or "vintage" Curtis gravures, they should not be considered "fakes" or "knock-offs." They are mostly fine archival photogravures made from Curtis’ original plates, often produced in limited editions. They therefore provide an affordable alternative to purchasing an original photogravure. (for in depth info see https://artvintage.tripod.com/index-204.html)

Reproduced / Exhibited

Curtis, Edward S. Native Nations. Boston: A Bulfinch Press Book, 1998. p. 12