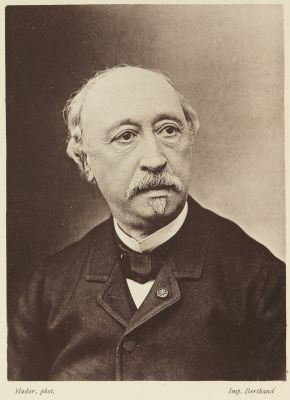

Title

Honore de BalzacArtist

Bisson, Louis-Auguste (French, 1840-1876)Publication

Paris-photographe : revue mensuelle illustrée de la photographie et des ses applications aux arts, aux sciences et à l'industrieDate

1891 plate (1842 negative)Process

PhotogravureAtelier

DujardinImage Size

10.5 x 7.7 cmSheet Size

27 x 18.2 cm

With this casual pose, originally intended for private use, Balzac defies every established convention in the field of the painted or the daguerreotyped portrait. He is pictured without a jacket, in shirt-sleeves and suspenders, with his collar open, as if he had been caught inadvertently in his study. His hand resting on his heart displays the ring that Madame Hanska had given him. This rare portrait of Balzac is reproduced here as a photogravure in Paul Nadar’s Paris Photographie, Vol 1, No. 2, 1891 and credited as based on a daguerreotype by his father Nadar (Gaspard-Félix Tournachon), however it was actually taken by Louis-Auguste Bisson in 1842 and is the only photographic image of Balzac, who had a well documented fear of being photographed.

Balzac was “daguerreotyped” by Bisson in May 1842, for his friend, Madame Hanska, who lived in a distant country. However, two identical yet reversed daguerreotypes remain, one of which can be found at the Maison de Balzac (passed down by Balzac), the other at the Institut de France. The second daguerreotype (with Balzac gazing to the left) had been owned by Nadar since 1863, after Camille Silvy. But he was already aware of it in 1854, when he used it as the basis for Balzac’s “caricature” in his famous Pantheon. Nadar was indeed passionate about Balzac, who had supported him when he was a young aspiring journalist, and who had died in 1850, before Nadar became a photographer. It is only under the pressure of financial difficulties that he sold the photograph in 1895 to Spoelberg de Lovenjoul, a collector who would in turn donate it to the Institut.

Nadar made a photographic copy of the daguerreotype plate (the negative of which is kept at the Médiathèque du Patrimoine). The reproduction was deemed too pale and was enhanced in order to bring out the shades. This version, retouched by hand, retained the original arched frame but erased the ring. It was included in Nadar’s demonstration album (kept at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France) and was reproduced as a heliogravure in the Paris Photographe review in 1891. It appears that these Nadar-made reproductions have not circulated a lot or even at all, for the pose seemed improper for a great writer. One of them has been obtained by Rodin in order to work on his famous sculpture: “I have looked at all the possible portraits of the author… In my opinion, this is the only true and faithful likeness of the illustrious writer. This plate is owned by Nadar and he has made a photograph of it. I have studied this document for a long time and today, as I hold it, I can say that I know Balzac, as if I had lived for years alongside him.”

Nadar writes about the portrait in the first chapter of When I Was a Photographer, his memoir published in Paris in 1900, and expands on Balzac’s reluctance to being photographed, supposedly because he believed that “specters” would detach from the sitter’s body to be printed on the plate (“Balzac and the daguerreotype”). [1] [2]

Reproduced / Exhibited

Coke, Van D. The Painter and the Photograph: From Delacroix to Warhol. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1972. pl. 118

Buerger, Janet E. French Daguerreotypes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989. no. 92.

Collections: musée d’Orsay, Paris Inventory number ODO 1996 55 84

References

[1] Buerger, Janet E. French Daguerreotypes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989.

[2] Philippe Jacquier from the Galerie Lumière des roses