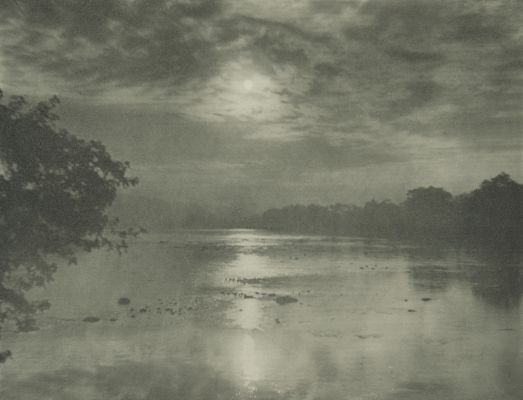

Title

“From Alabama”Artist

Eickemeyer, Rudolf (American, 1862 - 1932)Publication

The Photographic TimesDate

1898Process

Silver gelatin (Velox)Image Size

24 x 19 cmSheet Size

29 x 21 cm

Several developments brought on the amateur movement. The introduction of dry plates was the first and the most important. Dry plates put an end to the inconveniences of the collodion process, and their far greater sensitivity made "snapshot" photography possible. In 1884 George Eastman introduced the first practical roll film system, and four years later, the first Kodak camera. With the Kodak, anyone could practice photography with a minimum of preparation or trouble. The Kodak was sold containing film for 100 exposures; it was sent back to the dealer or to the Eastman factory for processing and printing and a fresh load of film. As amateur photography began to spread, manufacturers sought easy-to-use products to suit the new market. Among the most successful of the new products were the "gaslight" papers. One of the first to come on the market was Velox, in 1893. These gelatin papers, containing silver chloride, were less sensitive than bromide papers and could be handled easily in dim light. They were printed with the gaslight turned high and developed and fixed with the light turned low. Velox was the subject of an intense advertising campaign aimed principally at amateurs, and the paper was an enormous success. One reason was that Velox could be manufactured in various contrast grades to suit the widely varying negatives the amateurs produced. Velox Paper was first manufactured by Dr. Leo H. Baekeland in 1894 by the Nepera Chemical Company in Nepera Park, Yonkers, NY. Five years later, George Eastman of the Kodak company bought the Velox process from Dr. Baekeland for one million dollars and started to manufacture its own brand, also called Solio paper. [1]

This print is from the journal generally known as generally known as The Photographic Times, one of America’s earliest and most important photographic journals. The Times first appeared as a supplement incorporated within the pages of the monthly Philadelphia Photographer, one of the first journals devoted to photography published in America beginning in 1864. By 1889 issues were accompanied by well executed hand-pulled photogravure plates which appeared regularly until 1904. Due to changes in ownership or marketing strategies the name changed at least four times over the course of its 45 year run making keeping track of the specifics very difficult. This publication was an invaluable reference for the ever expanding photography movement in America at the turn of the century and published samples by the likes of Alfred Stieglitz, Gertrude Kasebier and Alvin Langdon Coburn. Initially it was geared to the professional photographer as would be expected, since it was published by the Scovil Manufacturing Co.; the articles mirrored their concerns. Reviews and reports from photographic societies were a regular feature. First edited by Edward Wilson, the editorship transferred to John Thraill Taylor, who enlarged the scope in 1880, when it became The Photographic Times and American Photographer. By 1882, an original mounted photograph was inserted, and in 1887, the size was increased to a large quarto, and fine photomechanical illustrations began appearing. It was becoming the preeminent American journal.

First published in 1871 as a supplement of The Philadelphia Photographer. It absorbed The American Photographer in 1879 to become The Photographic Times And American Photographer. In 1902, it merged with Anthony’s Bulletin to form The Photographic Times Bulletin. This periodical is most commonly cited as “The Photographic Times, Photographic Times Publishing Association. [2]

References

[1] Crawford, Keepers of Light, p. 63

[2] Many thanks to David Spencer for his research which can be found on Photoseed.com https://photoseed.com/blog/2012/11/25/march-of-trades-harmonious-shades-photographic-times/ (David Spencer, Photoseed)