Title

CoverArtist

Bradbury, Henry (British, 1831-1860)Publication

The Nature Printed British Sea WeedsDate

1859Process

Nature PrintAtelier

Bradbury, HenryImage Size

24 x 15.5 cm

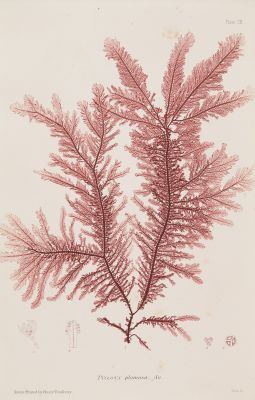

Capturing the exact details of a plant or insect by printing directly from the natural object had been a goal of printers for hundreds of years. Eighteenth century attempts to print directly from dried plants failed because the material was too fragile to withstand the printing process. In the nineteenth century, printers realized that they could first impress the object into another, harder material which could then be used to make the printing surface. Wood, softened by steam, and various types of metal were used to make a mold from the plants.

A successful process was developed in 1853 by Alois Auer, Director of the Government Printing Office of Vienna, and brought to England by Henry Bradbury. Termed nature printing. The process involved passing the object to be reproduced between a steel plate and a lead plate, through two rollers closely screwed together. The high pressure imbeds the object, for example a leaf, into the lead plate. When colored ink is applied to this stamped lead plate, a copy can be produced. Several colors could be applied individually, by hand, to appropriate areas of the plate and all colors printed together from one pull of the press. Very few books were actually printed by this method during the nineteenth century. The Ferns of Great Britain and Ireland, published in 1857 and The Nature-printed British Sea-weeds, published 1859-60 are the primary examples. The process was ideal for showing the thin two-dimensional fronds of ferns and seaweed, but less successful with more fleshy plants. Bradbury’s death in 1860, at the age of twenty-nine, seeded to end major interest in the process.

Reproduced / Exhibited

DiNoto, Andrea, and David Winter. The Pressed Plant. New York: Stewart, Tabori & Chang, 2000. p. 10