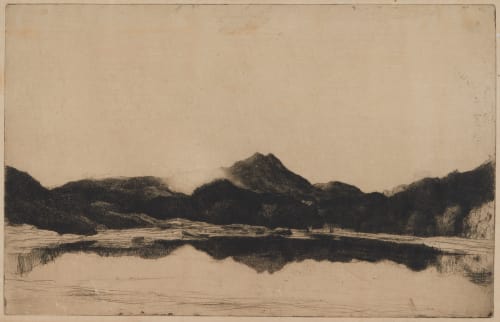

Title

Ben LomondArtist

Cameron, D.Y. (Scottish, 1865-1945)Date

1923Process

EtchingAtelier

D.Y. CameronImage Size

26 x 40 cm

Cameron was interested in portraying the grandeur and beauty of the Scottish Highlands, which he achieved through design rather than picturesque detail. He concentrated on the structure, tone and balance of the landscape. In this print Cameron shows the outline of Ben Lomond from across Loch Ard, but he has eliminated everything trivial to present a view of austere beauty that concentrates on the spirit of place. After giving up etching in 1917, Cameron took it up again in 1923 and then produced two of his greatest prints, this plate and the ‘Thermae of Caracalla’.

In the 1860s, graphic arts critics such as P.G. Hamerton and the etcher-critic Sir Francis Seymour Haden held that the essential quality of the etching was that of the hand drawn (but chemically etched) line which expressed the artist’s autographic and artistic intention, an attitude which clearly separated artist-etchers from the position of reproductive engravers. However, one of the artist-etcher James McNeill Whistler’s most important contributions to the Etching Revival was his ability to create tone, not just through fineness and density of lines but also by various means of expressive inking and wiping of the printing plate. His cultural and aesthetic impact on J.C. Annan’s etcher friends D.Y. Cameron and William Strang, and A.L. Coburn’s etcher mentor Frank Brangwyn, created a productive relationship between the etching and the pictorial photograph through its etched equivalent, the photogravure. [1]

Reproduced / Exhibited

National Galleries of Scotland Accession number: P 2325

References

[1] Hammond, A. (2009, September). The etching revival and the photogravure: A graphic aesthetic for photography. Paper presented at Impact 6 International Multi-Disciplinary Printmaking Conference