Title

Adam and EveArtist

Eugene, Frank (American, 1865-1936)Publication

Camera Work XXXDate

1910Process

PhotogravureAtelier

F. Bruckmann Verlag, MunichImage Size

17.7 x 12.7 cm

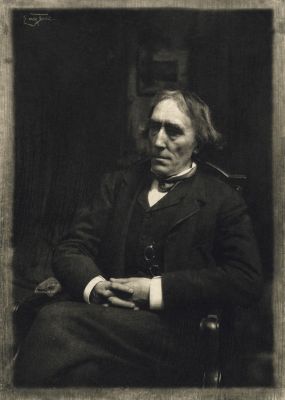

Born in New York to immigrant parents, Eugene was one of many young German-Americans to travel to Munich to study at the Royal Bavarian Academy of Arts. Alfred Stieglitz and the influential art critic Sadakichi Hartmann promoted Eugene’s Pictorialist photographs in exhibitions and publications such as Camera Work, where this photograph appeared in 1910. Eugene’s interest in a variety of artistic media is seen in the bold manipulation of his negatives. He used paintbrushes, etching needles, and pencils to rework his compositions, thus proclaiming their status as art. This photogravure depicts a classic subject from the annals of art history, the deep chiaroscuro and scratched surface suggesting Adam and Eve after the fall. [1]

“Eugene created a new syntax for the photographic vocabulary, for no one before him had hand-worked negatives with such painterly intentions and a skill unsurpassed by his successors.” [2]

Eugene’s unorthodox technique raised many questions regarding the line between painting and photography and manipulated photography as art. While Eugene’s methods clearly swam against the current of Emerson, Stieglitz and later Strand, he was championed as a Wunderkind of his time and was considered the first and only painter photographer and Stieglitz embraced his maverick method because Eugene’s photographs represented an esthetic reconciliation of these two camps [straight vs. manipulated] by amalgamating an element of practicality with the higher artistic ideal of achieving expressiveness through whatever means possible… All others think to accomplish their results, he feels [3] That print, printed as it is on Japan paper, conveys every impression of an etching, having the beautiful characteristics that one looks for therein : spontaneousness of execution, vigorous and pregnant suggestiveness, velvety color, and delightful evidence of the personal touch. There is nothing sacred in the mere process of etching of copper apart from its results. If similar results can be obtained some other way, and the artist chooses to adopt it because he finds it easier or more congenial, what concern is it of ours? The fact is, in this new art critics and photographers alike are feeling their way – they to expression and we to judgment. The art is still in the womb of time, its possibilities becoming wider and more appreciated; being new, one learns that the old standards and points of view do not necessarily apply to it, and more and more realize the need for an open mind. [4]

Of major importance for the acclaim of Eugen’s works was his participation in the New School of American Photography exhibition organized by Fred Holland Day and first shown in October/November 1900 in the rooms of the Royal Photographic Society in London, then in the Photo Club de Paris. The exhibition, which Stieglitz boycotted, represented a first impressive display of symbolist influences on the aesthetics of photography and included more than 400 works by Steichen, Coburn, Kasebier, Eugene, Day and others… It was in this exhibition that Eugene first presented one of his most famous photographs, “Adam and Eve,” which he took in 1898. Perhaps the reason for presenting this work so late was that the original negative had broken in three pieces and Eugene had tried to disguise the cracks with paintbrush and paint. The torso is a pictorial motif used repeatedly in symbolist art to focus on the incomplete, the fragmentary character of creation. Eugene’s photograph “Adam and Eve,” which has formal analogies with comparable depictions by Rodin or Stuck, was interpreted as the photographer’s strategy for legitimating the presentation of a male and female nude despite restrictive moral attitudes. This interpretation, however, neglects the actual theme of the photograph, namely, the representation of the first human couple. From the iconographical point of view, the modest turning of the head, which is etched over on the negative, hints more at a depiction of the Fall. Seen in this way, Eugene’s photograph can be interpreted as a symbolic expression of the irretrievable loss of paradise and the fateful beginning of the sexual entanglements between human beings. [5]

Reproduced / Exhibited

Dawm, Patrick, Francis Ribemont, and Philip Prodger. Impressionist Camera: Pictorial Photography in Europe, 1888-1918. London: Merrell Holberton, 2006. fig. 150

Doty, Robert M. Photo-secession: Photography As a Fine Art. N.Y: Eastman, 1960. p. 30

Ewing, William A. Love & Desire: Photoworks. London: Thames & Hudson, 1999. p. 96.

Marien, Mary W. Photography: A Cultural History. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: SunSoft Press, 2002. fig. 4.9.

Frizot, Michael. New History of Photography. Place of publication not identified: Pajerski, 1999. Print P. 322

Homer, William I, Catherine Johnson, and Alfred Stieglitz. Stieglitz and the Photo-Secession, 1902. London: Penguin Putnam, 2002. p. 14

Kicken, Annette, Georg Kargl, and Rudolf Kicken. Pictorialism: Hidden Modernism. Berlin: Kicken, 2008.p. 43

Kruse, Margret. Kunstphotographie Um 1900: D. Sammlung Ernst Juhl; Hamburg: Museum für Kunst u. Gewerbe, 1989 pl. 857

Pohlmann, Ulrich. Frank Eugene: The Dream of Beauty. Munich: Nazraeli Press, 1996. no. 34.

References

[1] Adam and Eve MET website cited 1/23 metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/260240

[2] Naef, Weston J. The Collection of Alfred Stieglitz: Fifty Pioneers of Modern Photography. New York: Viking Press, 1978. p.97

[3] ibid

[4] Caffin CH. Photography As a Fine Art the Achievements and Possibilities of Photographic Art in America. New York: Doubleday Page; 1901.p. 110

[5] Eugene, Frank, and Ulrich Pohlmann. Frank Eugene, the Dream of Beauty. Munich: Nazraeli Press, 1995 p. 51

Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York N.Y.) and Weston J Naef. The Collection of Alfred Stieglitz : Fifty Pioneers of Modern Photography. Metropolitan Museum of Art 1978.