Title

A Bit of VeniceArtist

Stieglitz, Alfred (American, 1864-1946)Key FigurePublication

The Photographic TimesDate

1898 plate (1894 negative)Process

PhotogravureAtelier

Photochrome Engraving Company, New YorkImage Size

18 x 12.2 cm

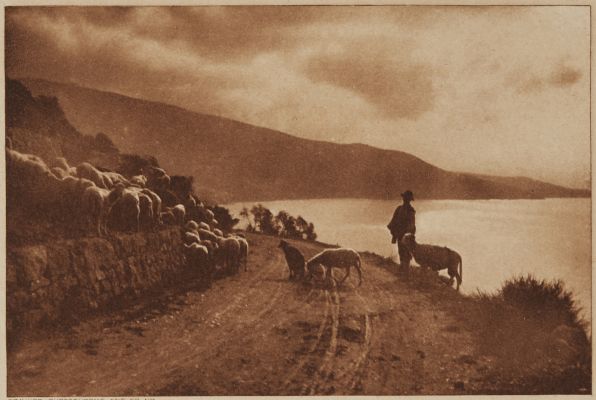

A Bit of Venice was photographed in the early summer of 1894 and published in New York several times later in the same decade. The striking photograph summarizes the results of Stieglitz’s nine years of study in Europe and represents the moment when the impact of his crusade on behalf of photography as an art form was first being felt in the United States. The photograph was taken during Stieglitz’s four-month European honeymoon in 1894 and his first trip to Venice since 1887. Shortly after his return to New York, Stieglitz created a photogravure from the negative. Clearly satisfied with the result, he published the image four times between 1897 and 1899 in influential photography magazines and books. In 1897 it appeared in the magazine Camera Notes and in Stieglitz’s portfolio Picturesque Bits of New York and Other Images. This print is from The Photographic Times of 1898. The photogravure was also included in the 1899 portfolio American Pictorial Photography, Series I published by the Camera Club of New York.

In its careful composition, use of soft focus, and straightforward printing methods, without manipulation or retouching, A Bit of Venice epitomizes the qualities sought in pictorial photography. At the forefront of circa-1890 European photography, pictorial photographers recognized that, while much was to be learned about composition and point of view through the study of contemporary painting, they could achieve effects with their cameras unattainable in any other medium. In his Venetian photographs, Stieglitz presents a point of view not unlike that to be seen in James McNeill Whistler’s much-discussed Venetian etchings (1879-80), but in A Bit of Venice he captures a damp mystery that could be suggested only with a camera.

The influence of European painting always lurks in Stieglitz’s images from the Venice honeymoon trip. The photographic negative provided Stieglitz with the raw material for the final photogravure. "My hand camera negatives are all made with the express purpose of enlargement and it is but rarely that I use more than part of the original shot," Stieglitz wrote in 1897, adding that "prints from the direct negative have but little value." His change of attitude over the years is evident in his reuse of the 1894 negative in the early 1930s in a gelatin silver print. Revealing that the 1897 photogravure represented only about a quarter of the original negative, the later more complete image lacks the mysterious quality of the photogravure. For example, one hardly notices the unsettling presence of the man coming through the distant arch at the right.

The caption to a later reprint of this image (Alfred Stieglitz, Photographs from the J. Paul Getty Museum [exh. cat., Malibu, 1995]) suggests that the photograph’s somber mood may reflect Stieglitz’s "first realization that he and [his wife] Emmeline [Obermeyer, who had loathed the stench of the canals and the shabbiness of the people who most interested Stieglitz as subjects] were motivated by quite different priorities." The marriage in fact lasted until 1924.

This photogravure is from the journal generally known as generally known as The Photographic Times, one of America’s earliest and most important photographic journals. The Times first appeared as a supplement incorporated within the pages of the monthly Philadelphia Photographer, one of the first journals devoted to photography published in America beginning in 1864. By 1889 issues were accompanied by well executed hand-pulled photogravure plates which appeared regularly until 1904. Due to changes in ownership or marketing strategies the name changed at least four times over the course of its 45 year run making keeping track of the specifics very difficult. This publication was an invaluable reference for the ever expanding photography movement in America at the turn of the century and published samples by the likes of Alfred Stieglitz, Gertrude Kasebier and Alvin Langdon Coburn. Initially it was geared to the professional photographer as would be expected, since it was published by the Scovil Manufacturing Co.; the articles mirrored their concerns. Reviews and reports from photographic societies were a regular feature. First edited by Edward Wilson, the editorship transferred to John Thraill Taylor, who enlarged the scope in 1880, when it became The Photographic Times and American Photographer. By 1882, an original mounted photograph was inserted, and in 1887, the size was increased to a large quarto, and fine photomechanical illustrations began appearing. It was becoming the preeminent American journal.

First published in 1871 as a supplement of The Philadelphia Photographer. It absorbed The American Photographer in 1879 to become The Photographic Times And American Photographer. In 1902, it merged with Anthony’s Bulletin to form The Photographic Times Bulletin. This periodical is most commonly cited as “The Photographic Times, Photographic Times Publishing Association. [1]

Reproduced / Exhibited

Alfred Stieglitz, "The Hand Camera: Its Present Importance," American Annual of Photography and Photographic Times Almanac for 1897, p. 19;

Richard Whelan in Alfred Stieglitz: A Biography (Boston, 1995), p. 119. 9. Los Angeles, Calif.,

The J. Paul Getty Museum, inv. 93.XM.25.55

References

[1] Many thanks to David Spencer for his research which can be found on Photoseed.com

Homer, William Innes. Alfred Stieglitz and the Photo-Secession. Boston, 1983.

Peterson, Christian A. Alfred Stieglitz’s "Camera Notes". Exh. cat., The Minneapolis Institute of Arts, 1993.

Whelan, Richard. Alfred Stieglitz: A Biography. Boston, 1995.

http://www.oberlin.edu/amam/Stieglitz_Venice.htm Turner