Title

Reflections: Night—New YorkArtist

Stieglitz, Alfred (American, 1864-1946)Key FigurePublication

Picturesque Bits of New York and Other StudiesDate

1897Process

PhotogravureAtelier

Alfred Stieglitz (film positive)Image Size

21 x 27 cmSheet Size

38.5 x 43 cm

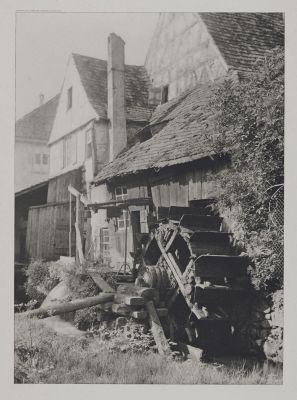

Photography in low-light conditions first became possible in the late 1880s with the introduction of the gelatin dry-plate process, which reduced exposure times significantly. After the English photographer Paul Martin showed his night photographs at the 1896 Royal Photographic Society exhibition and published his methods in the Amateur Photographer, night photography—taken without the benefit of additional gas or electric light—found many adherents. Stieglitz also tried his hand at the technique and was proud to report that in contrast to Martin’s exposure time of a half hour, his was a mere 58 seconds. Stieglitz’s innovation was to embrace, for pictorial purposes, what Martin attempted to conceal: “Paul Martin’s work shows an entire lack of halation around his lights, which, although speaking well for his technical skill in mastering the photographic bugbear halation, is a decided shortcoming from a pictorial point of view. We do not wish to say that halation galore improves night-work in which the illuminating source is included, but a certain amount of it certainly gives a more sincere and picturesque rendering of he object itself.” [1]. Halation offers the scene atmosphere, a hallmark asset of the photogravure syntax.

It was during Stiegitz’s years as editor of Camera Notes that he began exploring the artistic possibilities of photogravure. In 1897, the very year that Camera Notes commenced, the prestigious publisher R. H. Russell issued Picturesque Bits of New York and Other Stories, a portfolio of twelve of Stieglitz’s best-known early images printed as oversized photogravures. So important was this project to Stieglitz, that he personally made the transparencies used in plate making, and then supervised the printing of the entire edition of photogravures. So pleased was he with the results that he signed a limited deluxe edition of the portfolio and allowed the photogravures to be sold individually. Stieglitz felt these prints had high-art value and were no less intrinsically works of art because they were printed by photogravure. Such photogravures joined the great tradition of fine printmaking established by artists like Durer and Rembrandt. [2]

"We have been accustomed to see the fine tones and graduations of our best workers so utterly ruined in the process of engraving and printing that we are agreeably surprised at the wonderful delicacy and transparency of these examples. They are printed on heavy plate paper, 14×17 inches, and each plate is presented in a color appropriate to the subject. We might take exception to the tint employed in the “Glow of Night,” where the desire to reproduce the yellow glare of the incandescent and other lights glowing through the fog and mist of a rainy night on Fifth Avenue has led to the employment of colors that are singularly disagreeable. Perhaps our photographic experience heightens this repugnance, because the tones, ranging from yellow to a somewhat dirty greenish black, recall the effect of an aristotype badly sulphurized in a combined toning and fixing bath. It is possible that the print will be more satisfactory to an artist, or to an art lover, who has never dabbled in photography. In all the other cases the colors are admirably chosen." [3]

The photogravures were printed in an edition of twenty-five on plate paper using different ink colors. Stieglitz himself made the steel engravings from the diapositives (positives made from negatives) and used rapid plates to preserve the detail and softness of the originals. In addition, he directly supervised the printing of each image. Picturesque New York was apparently an earlier title of the portfolio. [4]

The pictures vibrate with atmosphere–fog, snow, streetlights reflected on wet pavements. The word “bits” suggests fleeting impressions caught by a highly selective eye, the crystallization of experience similar to the effects sought by Ezra Pound and Hilda Doolittle in the Imagistic poetry they would invent in the next decade. [5]

A two-page advertisement for the portfolio appeared in a small catalogue issued by publisher RH Russell in 1897 stating specifics for the portfolio as well as photographs, which Stieglitz sold individually. The twelve subjects, together with an introduction by W.E. Woodbury, are issued in an artistic portfolio. Price, $10.00 There will also be an Edition-De-Luxe in a special binding, limited to forty copies of the first impressions, each plate signed by Mr. Stieglitz. Price, $25.00 Single Proofs of any of the plates. Price, $2.00, each. Artist’s Proofs, signed by Mr. Stieglitz. Price, $5.00, each.

Even with this marketing push by RH Russell as well as others, it is doubtful that many of the Picturesque Bits portfolios were sold, especially the $25.00 Edition-De-Luxe edition signed by Stieglitz. Book seller catalogues around the turn of the 20th century remaindered original $10.00 “ordinary” copies of the portfolio to $5.00. The now accepted total copies of this seminal portfolio in the history of photography numbers a mere 25 copies: “The photogravures were printed in an edition of twenty-five on plate paper using different ink colors.” [6]

Reproduced / Exhibited

National Gallery of Art The Key Set 1949.3.247

Princeton University Art Museum x1982-22 f

Museum of Fine Arts Boston

Philidelphia Museum of Art 1968-68-4

SFMOMA

Greenough, Sarah, and Alfred Stieglitz. Alfred Stieglitz: The Key Set : the Alfred Stieglitz Collection of Photographs. Washington, D.C: National Gallery of Art, 2002.

References

[1] Alfred Stieglitz, “Night Photography with the Introduction of Life,” American Annual of Photography and Photographic Times Almanac for 1898, reprinted in Richard Whelan, ed., Stieglitz on Photography: His Selected Essays and Notes (Aperture, 2000), p. 83. (Art Institute of Chicago)

[2] Peterson Christian A et al. Alfred Stieglitz’s Camera Notes. 1st ed. Published by the Minneapolis Institute of Arts in Association with W.W. Norton 1993.

[3] William M. Murray, “Reviews and Exchanges: ‘Picturesque Bits of New York, and Other Studies,’” Camera Notes 1 (January 1898), 84–85.

[4] Lunn Photo-Secession: Catalogue 6 [exh. cat., Lunn Gallery, Graphics International Ltd.] (Washington, 1977), 124–125.

[5] Trachtenberg, Alan; Reading American photographs: Images as History: Mathew Brady to Walker Evans: 1989: Hill and Wang: New York: p. 184

[6] https://www.nga.gov/research/online-editions/alfred-stieglitz-key-set/portfolios-and-published-photographs.html