Title

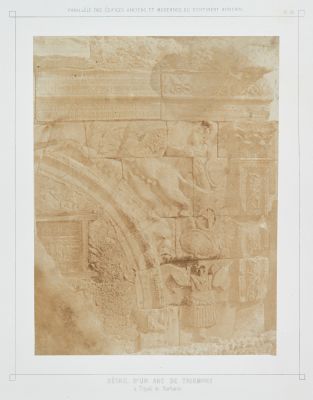

Pl. 50 Désert de l’isthme de SuezeArtist

Tremaux, Pierre (French, 1818-1895)Publication

Voyages au Soudan oriental et dans l'Afrique septentrionale, executes de 1847 a 1854Date

1854Process

Salt PrintAtelier

LemercierImage Size

19.5 x 24.7 cmSheet Size

35.7 x 55 cm

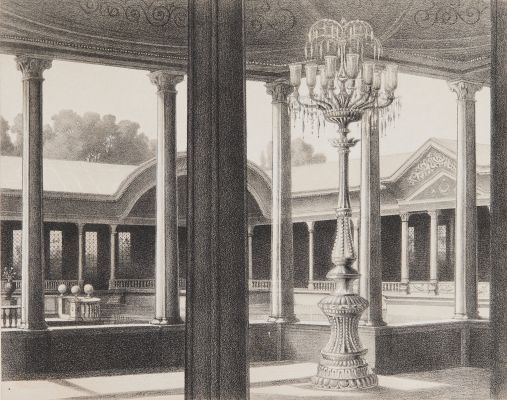

These luxe publications, produced with the support of the French government, exploit an array of graphic techniques; they combine salted paper prints, engravings, tinted and color lithographs, photolithographs, and texts in ways never previously attempted. Their examination provides insights into the ways these media interacted, and how comfortably photography in fact sat amongst its predecessors within the long-established context of the travel narrative. [1]

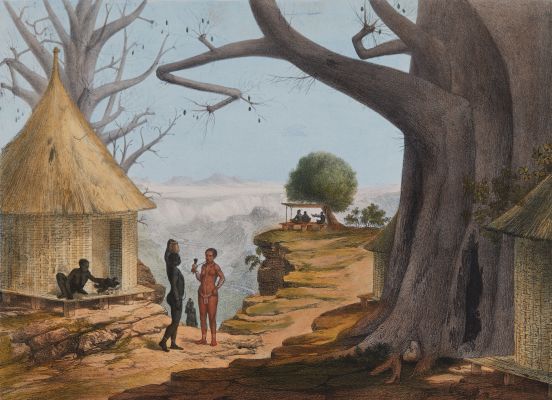

Architect, orientalist and photographer, Pierre Trémaux (1818-1895) made a first naturalist trip in 1847-1848 to Algeria, Tunisia, Upper Egypt, eastern Sudan and Ethiopia; Leaving Alexandria, he sailed up the Nile to Nubia and brought back many drawings. He left in 1853 for a second trip to North Africa and the Mediterranean (Libya, Egypt, Asia Minor, Tunisia, Syria and Greece), from where he brought back this time a precious set of superb photographs, taken on the spot using pioneering techniques for the time, as well as a fascinating travelogue and an interesting collection of natural history. The fruits of these travels were published in a series of books with very long titles. In abbreviated versions these were, Voyage au Soudan Oriental, Une Parallèle des Edifices Anciens et Modernes du Continent Africain and Exploration Archéologique en Asie Mineure. He illustrated the works with lithographs, original salt prints, and photolithographs after photographs using Poitevin’s process. This use of Poitevin’s process was due to the excessive fading of most calotypes originally issued in earlier installments of the work. Thus, only some issues of the book contain original salt prints from paper negatives. In other cases the photographs have been removed and in some instances the photlithographs were mounted on top of the original salt print. Unfortunately, Trémaux did not choose a master printer like De Fonteny (selected by Félix Teynard) to produce his calotypes, leading to excessive fading of most specimens.

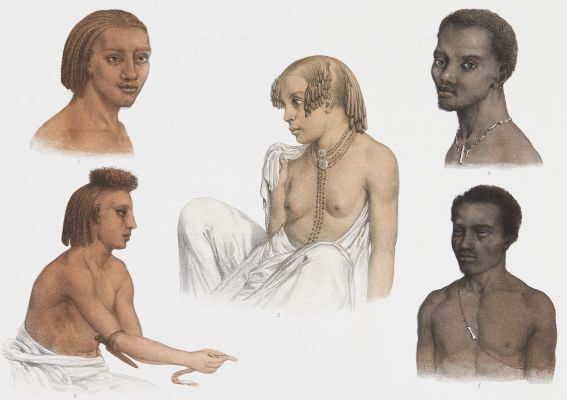

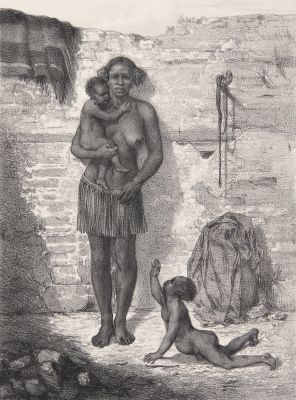

The poor condition, characteristic of most extant prints, makes it difficult to adequately assess Trémaux’s work. Despite the fading, some of the portraits rank among the earliest endeavors to record indigenous people by photography. Some examples are also artistically striking by today’s standards, the simplicity of the pose and the long exposure lending a raw primitive quality to the photographic efforts. Trémaux complained, typically, that the inhabitants of Islamic countries were not usually comfortable having their photographs taken. He persisted, however, revealing himself as one of the few early French photographers as interested in recording the people of a region as he was with its archaeological ruins. Trémaux was awarded for his work in 1864 with the coveted Legion of Honour.

The work was originally intended as a monumental work with a total of 355 photographs in the three series. However, the most complete set existing today includes only twenty-one photographs and fifty-six lithographs. Not only did the salt prints not withstand the effects of time (indeed, very short time), but from the surviving relatively good prints it seems that the negatives themselves were not of the best execution. In an apologetical note Trémaux wrote, the difficult circumstances under which they were produced has necessarily caused their relative mediocrity. It appears that these unsatisfactory results brought a premature end to the ambitious project. It is difficult to judge the artistic merits of his images from the photographs existing today. Nevertheless the project encapsulates the challenges facing the publication of permanent photographs in the mid 19th century.

References

[1] Kate Addleman-Frankel (2018) The Experience of Elsewhere: Photography in the Travelogues of Pierre Trémaux, photographies

The Art of French Calotype, with a critical dictionary of photographers, 1845-1870. André Jammes and Eugenia Parry Janis. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J. – 1983

First Seen, Portraits of the world’s peoples. Kathleen Stewart Howe. Santa Barbara Museum of Art – 2004

Odalisques & Arabesques: Orientalist Photography 1839-1925. Ken Jacobson. Bernard Quaritch Ltd. – 2007

French Primitive Photography. New York: Aperture, 1969. No. 154 – 157.