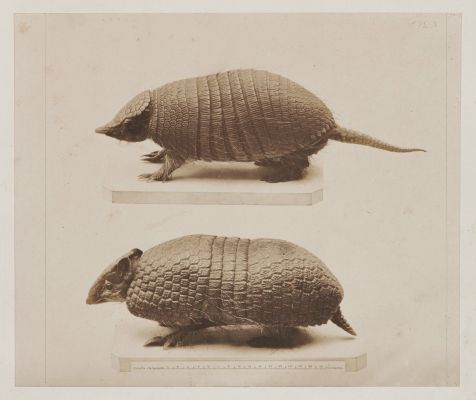

Title

CrustacesArtists

Bisson, Louis-Auguste (French, 1814-1876)Bisson, Auguste-Rosalie (French, 1826-1900)Publication

Photographie Zoologique Ou Représentation Des Animaux Rares Des Collections Du Muséum D'histoire NaturelleDate

1853Process

Photogravure (heliograph)Atelier

Mante and A. RiffautImage Size

20 x 27 cm

In 1852 the French Academy of Sciences decided to use photography to illustrate one of its studies examining the rare animals in the collection of the Museum of Natural History. La Lumiere treated it as a watershed in the developing relationship between photography and science. The first fascicles of the volume were issued with salted paper prints by the Bisson frères tipped in, but in 1853 the Academy switched to Niépce de Saint-Victor’s newly announced photogravure (heliographic) process. Members of the academy favored the new printing process over the silver-based calotype because the ink-based method was permanent. Cousin of the pioneer of the medium, Abel Niépce de Saint-Victor returned to the principles of Niépce’s Cardinal d’Amboise and, again like the elder Niépce, worked with the master printer Lemaître to perfect his heliographic process.

The volume is thus the first substantial publication to be illustrated with photogravures.

Writing about the book’s photogravure plates in his summary of photography at the Universal Exposition of 1855, Ernest Lacan declared that Dès maintenant, il est prouvé que la gravure héliographique peut se prêter à toutes les applications de la photographie… Bientôt, nous en sommes convaincu, elle amènera une véritable révolution dans la librairie. Un jour viendra, en effet, où l’historien, le voyageur, le naturaliste, ne voudront plus confier l’illustration de leurs livres qu’aux graveurs héliographes. (From now on, it is proved that heliographic engraving can lend itself to all applications of photography … Soon, we are convinced, it will bring a real revolution in the bookstore. A day will come, in fact, when the historian, the traveler, the naturalist, will no longer wish to entrust the illustration of their books to the engravers.) More surprising than that, this most enthusiastic critic and publicist for photography declared that Pour nous la photographie, si complète qu’elle soit dans ses résultats, n’est qu’un procédé transitoire, et c’est à la gravure héliographique ou à la photolithographie qu’appartient l’avenir. (For us photography, so complete as it is in its results, is only a transient process, and it is to gravure or photolithography that the future belongs.)

The application of an aquatint ground directly onto the bare metal plate before emulsion coating was described by Talbot in his patent of 1852. This approach was modified in May 1853 and incorporated into the heliogravure process devised by Niepce de Saint-Victor and Lemaître. Their technique called for resin-dusting the partially etched heliographic plate which was then mildly heated to soften the resin particles and adhere them to the surface. The plate was then etched to completion. While it was intimately connected to older graphic traditions of printing multiples like etching and lithography, Niépce and Lemaître’s process remains an essential origin point for both photography (images made with the action of light) and photomechanical printing (images made with the action of light printed in ink).

Graphic art printers, as well as political economists and industrialists, used their respective trade journals to promote the project as the first practical test for photogravure while officials of the Muséum d’histoire naturelle also promoted Photographie Zoologique as the first institutional attempt to apply the medium of photography to a systematic cataloguing effort. The project therefore occupied more than one seat at the table of new photographic applications.

References

Bann, Stephen. “Photographie Et Reproduction Gravée: L’ Économie Visuelle Au Xixe Siècle.” Etudes Photographiques / Société Française De Photographie. (2001): 22-43. Print.

Comptes Rendus Hebdomodaires des Sceances de I’Academie des Sciences, Note sur la gravure heliograptiique sur plaque d’acier. C. F- A. Niepce de Saint-Victor (May 23, 1853)

Correspondence between Joseph-Nicéphore Niépce, at Chalons, and M. Lemaitre, engraver at Paris, La Lumière, 1851, n. 1-9. Letter, January 1, 1827.

Eder, Josef M, and Edward Epstean. History of Photography. New York: Dover Publications, 1978.

Frizot, Michel, Aubenas, Sylvie The Photograph in Print, Multiplication and Stability of the Image. A New History of Photography, 1999

Gernsheim, Helmut. The Origins of Photography. London: Thames and Hudson, 1982 p. 37

Hammann, J.-M.-Herman. Des Arts Graphiques Destinés a Multiplier Par L’impression: Considérés Sous Le Double Point De Vue Historique Et Pratique. Genève [etc.: JoëlCherbuliez, 1857 P. 451

Rosen, Jeff. “Naming and Framing ‘Nature’ In Photographie Zoologique.” Word & Image. 13.4 (1997): 377-391.

Rosen, Jeff The Printed Photograph and the Logic of Progress in Nineteenth-Century France Jeff Rosen Art Journal, Vol. 46, No. 4, The Political Unconscious in Nineteenth-Century Art (Winter, 1987), pp. 305-311

The Evolution of the Modern Lens. Address of the President, Mr. T. R. Dallmeyer, F. R. A. S., Etc., before the Royal Photographic Society, London, October 9, 1900. Reprinted from “The Photographic News.” (Anthony’s Photographic Bulletin, Volume 31: 384).

Translation of Niépce de St. Victor article from the 31 October 1853 issue of La Lumière on heliographic engraving on steel plates appears in The Photographic and Fine Art Journal [7:3 (March), pp. 76-77] and later that year in Humphrey’s Journal[6:16 (Dec. 1), pp. 241-45].

Towler, John. The Silver Sunbeam. Joseph H. Ladd, New York: 1864 CH 40

The Photographic News. Place of publication not identified: publisher not identified, October 19, 1900.

Thierry Laugée, "Zoological Photography, Achille Devéria and Louis Rousseau", BNF Review 2017/1 (No. 54), p. 120-129